Running Head: Roflumilast or Azithromycin for COPD

Funding Support: Research reported in this publication was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (PCS-1504-30430). This project was also supported by Task Order HHSF22301011T under Master Agreement HHSF223201400030I from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Date of Acceptance: December 19, 2025 | Published Online Date: January 5, 2026

Abbreviations: CMS=Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FDA=U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HIPAA=Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HTEs=heterogeneity of treatment effects; HR=hazard ratio; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; IRB=institutional review board; LABA=long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA=long-acting muscarinic antagonist; PDE=phosphodiesterase; PROMIS=Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; RELIANCE=RofLumilast or Azithromycin to preveNt COPD Exacerbations study; RWE=FDA’s Real-World Evidence; SABA=short-acting beta2-agonist; SAMA=short-acting muscarinic antagonist

Citation: Krishnan JA, Holbrook JT, Sugar EA, et al. Rationale and design of the roflumilast or azithromycin to prevent COPD exacerbations clinical trial. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2026; 13(1): 17-28. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0669

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (922KB)

Introduction

The public health burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is substantial, most of which is due to respiratory infections or inhaled irritants that lead to airway inflammation and worsening dyspnea and cough (COPD exacerbations).1-4 Among patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations in the United States, the 12-month rehospitalization and mortality rates are about 64% and 26%, respectively.5 Chronic bronchitis, defined as chronic cough and sputum, identifies a subgroup of people with COPD with an especially high risk of exacerbations and death.6,7

In patients who continue to have exacerbations despite inhaled maintenance therapy, treatment escalation with long-term oral azithromycin or oral roflumilast is recommended to reduce the risk of COPD exacerbations on the basis of placebo-controlled clinical trials.4,8,9 Long-term (3 to 12 months) use of oral azithromycin, a macrolide with immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial effects to prevent COPD exacerbations is an example of an evidence-based “off-label” use of an U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medication.10-13 Roflumilast, a long-acting oral selective phosphodiesterase (PDE)-4 inhibitor with anti-inflammatory effects, was approved by the FDA in 2011 as a treatment to reduce the risk of COPD exacerbations in patients with COPD associated with chronic bronchitis.14-17 The FDA-approved indication for roflumilast is limited to patients with COPD associated with chronic bronchitis because the protective effects of roflumilast compared to placebo on exacerbations appear to be specific to this COPD subgroup.18

The relative harms and benefits of adding azithromycin versus roflumilast to current therapy in COPD are unclear as there are no clinical trials directly comparing the 2 treatments. Such information would address clinical uncertainty among patients and clinicians about which medication to use,19 including efforts to reduce the risk of readmissions and death in patients hospitalized with severe COPD exacerbations.20,21 In this report, we present the design of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute-funded, investigator-initiated, multicenter, stakeholder-engaged, pragmatic trial (RofLumilast or Azithromycin to preveNt COPD Exacerbations [RELIANCE] study) to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of treatment escalation with long-term azithromycin versus roflumilast in patients with COPD and chronic bronchitis.22

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Chicago Area Institutional Review Board (IRB), which served as a single IRB for most clinical centers. Local IRB approval was required from some clinical centers. The RELIANCE clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04069312) was launched in February 2020.

Stakeholder Engagement

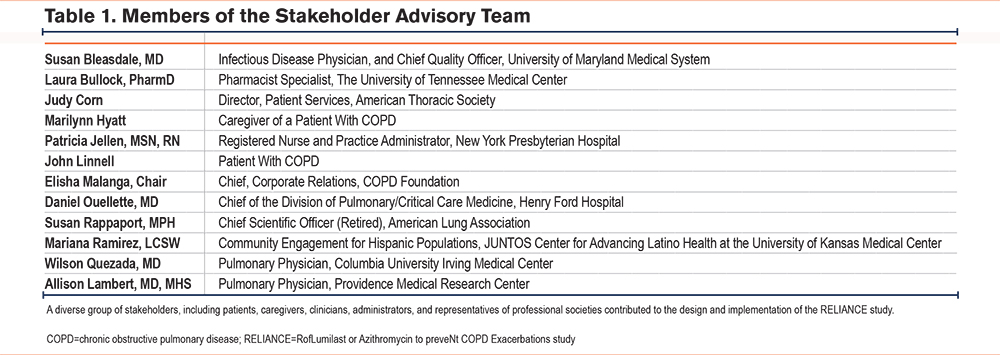

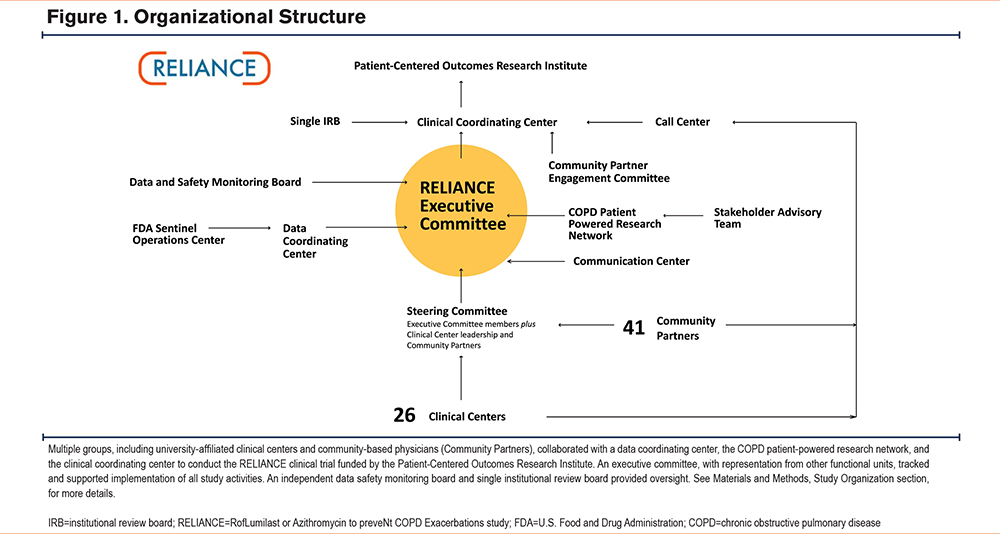

The RELIANCE clinical trial leadership engaged end-user stakeholders early in the planning phase to ensure that study results would address knowledge gaps relevant to their expressed needs. With the help of the COPD Foundation, we elicited input from patients with COPD, their caregivers, and pulmonary physicians to identify endpoints that would drive decision-making at the point of care and confirm sufficient community-level clinical equipoise to implement a randomized clinical trial.19 Of 196 patients or caregivers, 62% indicated they would work with researchers on a study comparing roflumilast and azithromycin. There was also community-level equipoise among practicing physicians: a survey of 43 pulmonologists indicated preferences for azithromycin in 30%, roflumilast in 9%, and no preference in 60%. The study also included a “Stakeholder Advisory Team” that met once per year to inform study design and implementation considerations (Table 1), including amendments to the study protocol to address barriers to enrollment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Representatives from the Sentinel Operations Center and from the FDA’s Real-World Evidence (RWE) program participated as observers in RELIANCE executive committee (Figure 1) meetings to promote shared learning and to provide an understanding about the use of real-world data (data relating to patient health status and/or the delivery of health care routinely collected from a variety of sources) to generate RWE.23-25

Patient Population

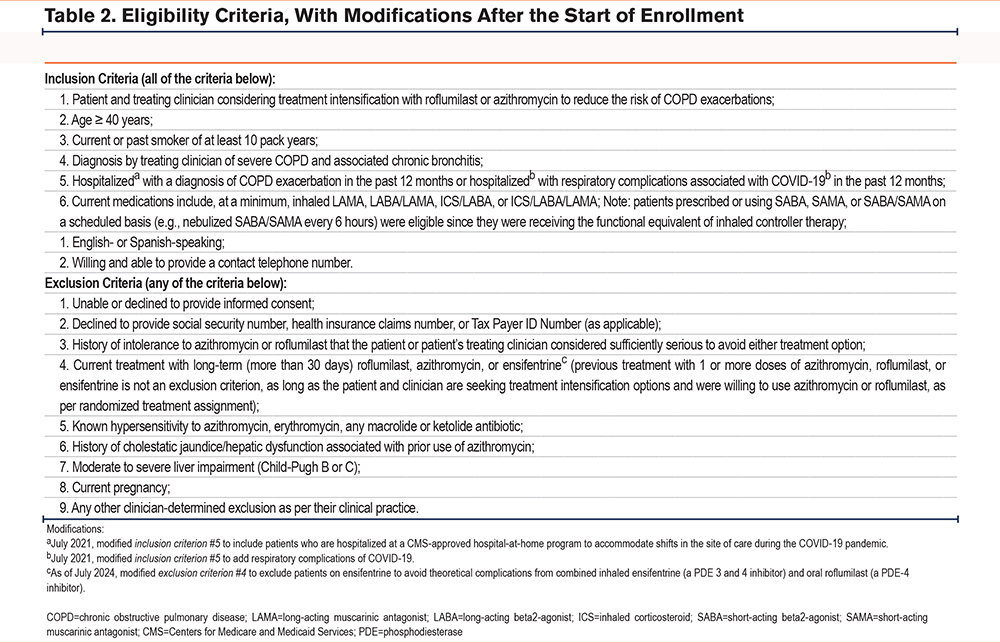

Eligibility Criteria

The RELIANCE clinical trial intended to recruit a representative group of patients with COPD in whom long-term azithromycin or roflumilast was clinically indicated as a treatment intensification.4,8,9 Eligibility criteria (Table 2) were intended to select individuals with COPD at high risk of hospitalizations or death who could be treated with either medication in clinical practice, with exclusions principally for safety as specified in the FDA prescribing information for roflumilast and azithromycin.10,14 In keeping with the principles of pragmatic trials, the eligibility criteria did not require assessments outside of standard clinical practice.26 Clinical trials to date establishing the efficacy of azithromycin and roflumilast in COPD excluded patients with concomitant asthma.11,16 While such exclusions have been customary in placebo-controlled efficacy trials to minimize heterogeneity among study participants, it is increasingly recognized that individual patients may have features of both COPD and asthma. Patients with a physician diagnosis of both asthma and COPD were, therefore, eligible to participate in the RELIANCE study.

Recruitment

The original approach to recruitment utilized university-affiliated clinical centers. Patients were approached by their physician in person during an outpatient visit or during a hospitalization (recruitment embedded in clinical practice). Written informed consent was obtained in person using IRB-approved materials by the treating physician or other study staff.

Modification to Eligibility Criteria and Recruitment

During the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person outpatient visits were suspended at many clinical centers as part of infection control precautions.27 Telehealth was promoted as a substitute for in-person outpatient care.28 Pulmonologists, many of whom were involved in the evaluation and management of patients with COVID-19, were unable to continue their research in COPD. In addition, the availability of hospital beds was limited due to the surge in hospitalizations for COVID-19-related respiratory complications. Various clinical centers also implemented severe restrictions in most research activities to focus on federal and industry-sponsored COVID-19-related research. These clinical and research restrictions slowed enrollment into the RELIANCE study.

Community Partner Referral Pathway

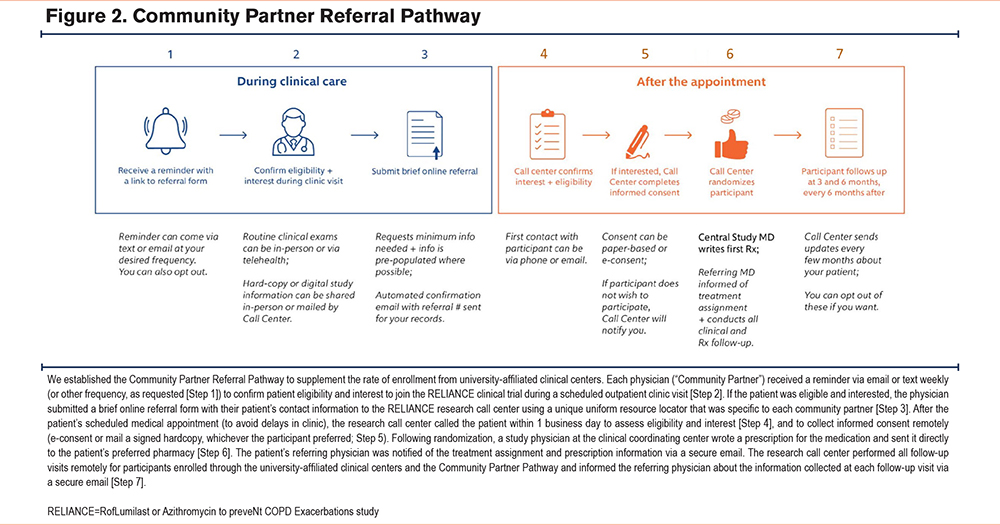

As a result, the study protocol was amended to include a “Community Partner Referral Pathway” to engage patients and their treating physicians in community-based settings, including practices without dedicated research staff to obtain informed consent (approved in June 2021, after 127 participants were enrolled). Engagement of patients and treating physicians in community-based practices was expected to increase the overall rate of enrollment into the study while also improving the generalizability of study results by enrolling patients in the clinical trial who might not otherwise participate in COPD research.

To be eligible to join the RELIANCE study as a community partner, the physician had to be referred by a RELIANCE investigator. The onboarding process included a review of materials about the RELIANCE clinical trial and the community partner’s role in identifying and referring eligible patients to the centralized research call center. In the Community Partner Referral Pathway (Figure 2), a practicing physician who was considering treatment intensification for a patient and had clinical equipoise about whether to prescribe roflumilast or azithromycin could submit an online, IRB-approved referral form to the call center (Supplemental Figure 1 in the online supplement). In the referral form, the physician was asked to attest that their patient met all eligibility criteria and was interested in learning more about the RELIANCE clinical trial. Physicians were also asked to provide the patient’s preferred contact information.

The call center then called the patient within one business day to obtain written informed consent via e-consent or via paper, as per patient preference. After obtaining informed consent, the participant was randomized, and a study physician then submitted an e-prescription to the patient’s preferred pharmacy for a 30-day supply of either roflumilast or azithromycin depending on the treatment assignment. The referring physician was notified via secure email about the randomization and after the prescription is submitted to the pharmacy. The referring physician is also sent a secure e-mail reminder to write subsequent prescriptions for the medication, as clinically indicated. The final list of clinical centers and physicians using the Community Partner Referral Pathway is provided in the Supplement Table 1 in the online supplement.

Changes in Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were amended to broaden the definition of hospitalization to include hospitalization for respiratory complications from COVID-19 in a patient with COPD,29 and hospitalization through Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Acute Hospital Care at Home initiative. Both amendments occurred in July 2021, after 137 participants were enrolled. In June 2024, the FDA approved the use of inhaled ensifentrine, a PDE-3 and PDE-4 inhibitor, for the maintenance treatment of COPD.30 In July 2024, use of ensifentrine was added as an exclusion criterion to avoid theoretical complications from the combined use of inhaled and oral medications that both inhibit PDE-4.

Study Organization

The study consortium (Figure 1) consisted of: (1) a clinical coordinating center responsible for communication and contracts with all study partners, preparing progress reports to the funder, and regulatory submissions to the single IRB; (2) a centralized research call center to conduct virtual follow-up visits and to obtain informed consent through the Community Partner Referral Pathway; (3) a data coordinating center responsible for data collection forms, data management, performance reports, and statistical analysis; (4) a communication center to develop participant and clinician-facing study materials fit for purpose at university-affiliated sites and community-based practices; (5) a single IRB through the Chicago Area Institutional Review Board (IRB 00009693); (6) the COPD Patient-Powered Research Network led by the COPD Foundation to engage the patient community to raise awareness, provide updates, solicit feedback about study activities, manage the stakeholder advisory team, and host the clinical trials management software (DatStat); (7) an independent data safety monitoring board to review safety and study performance; (8) a steering committee that provided overall governance for the trial with voting members including representatives from clinical centers and the Community Partner Referral Pathway, plus leadership of the clinical coordinating center, data coordinating center, and COPD Patient-Powered Research Network; (9) an executive committee that tracked and supported implementation of study activities; and (10) a community partner engagement committee that included representatives of the Community Partner Referral Pathway to identify approaches to engage busy clinicians in research at the point of care.

Study Treatments

Previous clinical trials employed various regimens for azithromycin (250mg/day,11 500mg/day 3 times per week,12 or 500mg/day for 3 days during hospitalization then 250mg every other day13) or roflumilast (500mcg/day,15-17 250mcg/day for 4 weeks, then 500mcg/day19). The patient’s physician could initiate treatment with any of the regimens above or with an alternative regimen that was tailored to the patient’s clinical needs and preferences (e.g., starting with a lower dose or a different dosing schedule). Decisions about treatment alterations after randomization were also left to the discretion of the participant’s treating clinicians.

Consent and Randomization

All patient-facing materials and tools were submitted for IRB review prior to use. Consent (in-person or remote) was obtained by the clinical center or by the call center for the Community Partner Referral Pathway. Participants were randomly assigned to receive a prescription for azithromycin or roflumilast (1:1 allocation ratio), stratified by location (one for each clinical center and one for the Community Partner Referral Pathway) and smoking status (current versus former). Treatment assignment was revealed after eligibility was confirmed and consent was obtained (concealed randomization). After the treatment assignment was made, the participant remained in the study until completion regardless of treatment adherence.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome is the composite of all-cause first hospitalization or all-cause death. We selected all-cause events, rather than COPD-related events, as the primary outcome because it is difficult to attribute hospitalization or death to a particular underlying diagnosis in patients with multiple chronic conditions. Secondary outcomes include the individual components of the composite outcome and COPD-related acute care events (hospitalization, emergency department visit, or urgent care visit). Due to comorbid conditions (e.g., heart failure), attributing acute care events to COPD may be less reliable than all-cause events. Additional secondary events include patient-reported physical function, sleep disturbance, fatigue, anxiety, and depression; adverse events, medication adherence, crossover from one study arm to the other, treatment discontinuation; and out-of-pocket costs.

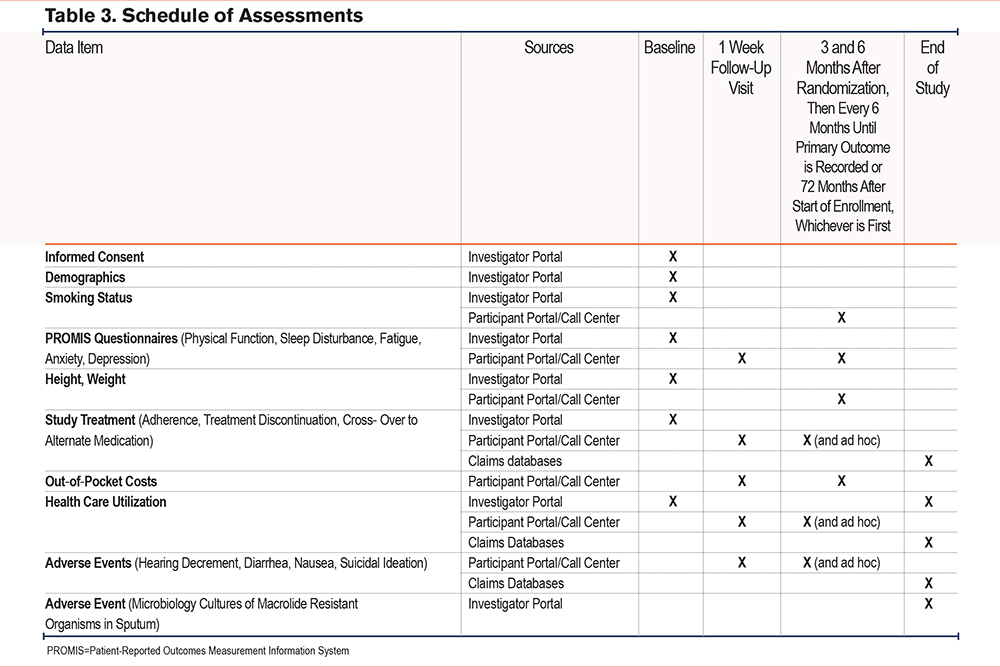

Data Collection and Schedule of Assessments

There were no required in-person visits outside of normal clinical practice. Baseline data required for enrollment and randomization were collected by the clinical center or by the call center for participants enrolled through the Community Partner Referral Pathway (Table 3). Participants had the option of completing follow-up surveys through an online participant portal or being contacted by the call center via telephone. Follow-up data for the primary outcome were collected via participant portal, the call center, and ad hoc reporting by study coordinators on the investigator portal. All calls involving the call center were recorded for quality assurance and training purposes using Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant telephony software (Five9, Inc.; San Ramon, California) integrated into the call center’s Voice over Internet Protocol system. Recordings were stored locally on a HIPAA-compliant secure server where they will be available for up to 3 years after final data analysis and publication of the primary manuscript are complete.

Participants were queried by phone or via online portal (per participant preference) 1 week after randomization to determine if they filled their prescription for the study treatment, and if so, the out-of-pocket cost. Participants were then queried at 3 months and 6 months after randomization during the first year of participation, and then every 6 months until a primary outcome (all-cause hospitalization or death) was observed or the study ended. The minimum study follow-up was 6 months, regardless of whether a primary outcome was observed and the maximum study follow-up was originally 36 months but subsequently increased to 72 months. Study coordinators were asked to assist in locating participants who were lost to follow-up and in ascertaining or verifying hospitalizations and death via review of electronic health records. Study coordinators also submitted data pertaining to adverse events, all-cause hospitalization, changes to study medications, medical diagnoses, or other relevant information.

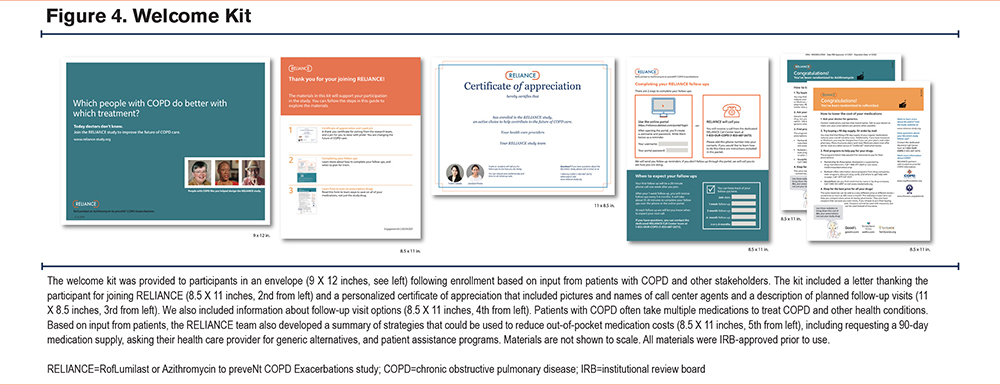

Participant Retention Strategies

We incorporated several strategies to enhance retention. We engaged stakeholders early and continuously in the planning and implementation of the study. A patient was included on the study’s executive committee, and a stakeholder advisory team with diverse perspectives was established to ensure that study activities were informed by the needs and preferences of people with the lived experience of COPD and those who care for them. Participant burden was minimized by not requiring in-person follow-up visits and collecting information via brief questionnaires (about 15 minutes). We provided participants information about the study’s public website,31 which included the perspective of patients, caregivers, and clinicians about the RELIANCE clinical trial and a description of the study team, enrollment updates, and video recordings about advances in the management of COPD. Also, participants were given a lapel pin and a certificate of appreciation, since participants often expressed pride about their contributions to a national study of COPD.

Promoting Usability

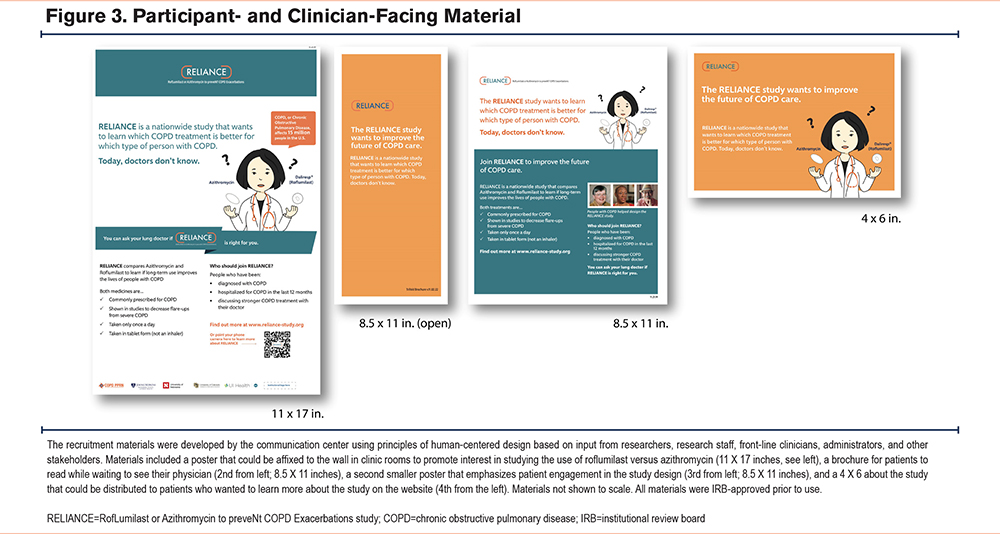

Usability is a concept used in human-centered design that refers to the degree to which an experience is or is not frictionless in the context of use.32,33 The RELIANCE communication center employed human-centered design to improve the usability of study activities from the perspective of participants, study staff, and treating clinicians. The communication center was responsible for the development of participant and clinician-facing study materials, including posters, flyers, consent forms, and other communication artifacts specific to different university-affiliated and community-based practices (Figure 3). Newly enrolled sites also received a welcome kit to orient them to the study and guide them through key messages to communicate to potential participants (Figure 4).

Statistical Analysis Plan

RELIANCE employed a randomized open-label parallel group comparative effectiveness trial design to evaluate whether azithromycin was noninferior to roflumilast in high-risk patients with COPD for prevention of hospitalizations or death.34,35 Our choice of a noninferiority margin of 1.2 was based on a clinical trial in COPD.36 Secondary sensitivity analyses included per-protocol analyses (i.e., the subgroup of patients who adhere to their assigned treatment), since noninferiority designs can be anticonservative in cases of crossovers or lack of adherence to study treatment. Data on protocol performance such as treatment adherence, losses to follow-up, and missing data will be used to help understand and interpret differences, if any, in the results of the 2 methods.37,38

The primary outcome is the time to first all-cause hospitalization or death. Individuals without an event will be censored at the date of last contact. A Cox proportional hazards model will be used to assess whether azithromycin is noninferior to roflumilast. If noninferiority is achieved, then an additional test for superiority will be performed. The primary analysis will adjust for smoking status and location (stratification variables) through the inclusion of fixed and random effects, respectively.

A test of interaction will be used to assess the potential for heterogeneity of treatment effects (HTEs) based upon smoking status (current versus former). Secondary analyses will also include adjusting for and investigating potential HTEs for key baseline characteristics including but not limited to 3 specified comparisons: (1) a history of asthma (yes versus no), (2) gender (male versus female), and (3) obesity (obese versus not obese). Analysis of secondary outcomes (e.g., patient-reported adverse events, physical function, anxiety, and medication adherence) by treatment group will employ negative binomial, logistic, linear, and Cox proportional hazards models for event rates, binary outcomes, continuous outcomes, and time to event outcomes, respectively. Mixed-effects models will be used to examine outcomes with repeated measurements over time and to adjust for the location stratification variable. Both unadjusted and adjusted models including the stratification variables (location and smoking status) as well as clinically important risk factors (e.g., history of asthma, medication use) will be explored. Summary statistics, model estimates with confidence intervals, and p-values will be used to present the findings. Analyses will be performed to assess model assumptions.

Adherence

Adherence is based on participant self-report, consistent with clinical practice. The degree of adherence is an important factor for interpreting the results of the intention-to-treat analysis as well as serving as the basis for per-protocol analyses. However, analyses relying on postrandomization variables are likely to be biased or require complex mathematical models with numerous assumptions.37,39 Individuals will be classified according to a number of different methods (e.g., any adherence [at least one usage], minimum adherence [above a certain threshold]) for sensitivity analyses. A variety of causal inference techniques, including inverse probability weighting methods will be used to assess the impact of adherence.

Sample Size

Noninferiority will be achieved if the upper boundary of the 2-sided 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio (HR) (azithromycin/roflumilast) is less than the noninferiority margin based upon a Cox proportional hazards model after adjusting for the stratification variables. This is equivalent to having a 1-sided type 1 error rate of 0.025. The planned recruitment period was 66 months with an additional 6 months of follow-up. In the original study design, we estimated that 3200 participants would be needed to provide 92% power with a 1-sided type 1 error of 0.025 to establish noninferiority based on a study-wide event rate for the primary outcome of 30% at 12 months and log-rank test with a margin of HR = 1.2 (azithromycin: roflumilast) assuming: (1) the true HR = 1, (2) the cumulative percentage with an event at 1 year was 30%, (3) a follow-up period of 36 months; and (4) a 5% loss to follow-up per year (14.3% cumulatively).

Due to slower than expected enrollment during the COVID-19 pandemic, the data and safety monitoring board requested a review of the feasibility of reducing the sample size based on observed event rates in May 2022. Review of pooled masked data indicated that the cumulative incidence of the first all-cause hospitalization or death at 12 months was about 60%, which was approximately twice the expected rate at the start of the study. The data and safety monitoring board approved a reduction in sample size to 1250 (934 events) and an increase of the maximum study follow-up to 72 months, which together provides 82% power with a 1- sided type 1 error of 0.025. Analyses were computed using R (version 4.2.3), PASS software (version 15.0.13), and SWOG Statistical tools.40,41

Interim Analyses

A single, formal, interim efficacy analysis was planned following collection of 50% of the information (i.e., 467 of the expected 934 events of all-cause hospitalization or death have been observed with the updated sample size). The trial would be stopped early only if 1 of the 2 treatments is demonstrated to be superior (i.e., it would not be stopped if the noninferiority criteria were met). Based upon an O'Brien-Flemming type boundary, the type 1 error rate would be 0.00305 for the interim analysis and 0.04695 at the final analysis to maintain a global 0.05 error rate over the course of the trial for the superiority comparison.

Risk-Based Monitoring

A risk-based monitoring plan prioritized audits at points of greatest risk to data integrity and participant safety.42 We audited the dates of the qualifying COPD-related hospitalizations by requesting source documents in a random sample of 20 participants from the highest 2 enrolling clinical centers and 7 community partners. We also reviewed a random sample of 6 recorded calls by the call center agents who were obtaining informed consent in 2 participants recruited through the Community Partner Referral Pathway and 4 completed follow-up visits among participants enrolled through clinical centers or the Community Partner Referral Pathway. We also reviewed recorded calls on an ad-hoc basis when participants reported suicidal ideation, had difficulty responding to questions via phone, or requested withdrawal from the study. To date, we identified protocol deviations in 3 participants (enrolled by 2 different community partners) due to inadequate documentation of a qualifying hospitalization for COPD exacerbation in the previous 12 months; the 2 enrolling community partners reported that dates of hospitalizations at outside health systems were difficult to discern accurately in electronic health records. The 3 protocol deviations were reported to the single IRB, and all community partners were retrained on study eligibility criteria. The online referral form (Supplemental Figure 1 in the online supplement) for the Community Partner Referral Pathway was modified to include the date of the qualifying hospitalization. No other protocol deviations from this approach to risk-based monitoring have been identified as of the date of this report.

Discussion

The RELIANCE study is an investigator-initiated, stakeholder-engaged, multicenter trial to compare the effectiveness of treatment escalation with long-term roflumilast or azithromycin in patients with COPD and chronic bronchitis in clinical practice. We solicited feedback from multiple stakeholders, including patients, clinicians, administrators, and professional societies, during the design and implementation phases of the study, including modifications related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The COPD Foundation, an advocacy group representing patients with COPD, played a central role in implementing the RELIANCE study by leading efforts to engage the patient community, managing the broader stakeholder advisory team, and hosting the clinical trials management software. Representatives from the Sentinel Operations Center and from the FDA’s RWE program also participated as observers to promote shared learning about the use of real-world data.

The original study design relied on in-person recruitment during routine patient care at university-affiliated clinical centers, in-person consent, and prescribing roflumilast or azithromycin according to the randomized treatment assignment. Participant burden was minimized by conducting follow-up visits remotely via an online portal or phone, and abstraction of electronic health records. An unconventional aspect of the study was the engagement of patients and treating physicians in community-based practices who might not otherwise participate in research (the Community Partner Referral Pathway) to increase the overall enrollment rate in the study.43 The Community Partner Referral Pathway is also expected to improve the generalizability of the study results. The final study design offered the option for remote consent as part of a decentralized trial infrastructure to engage patients with COPD with a particularly high rate of hospitalizations and death (about 60% at 1 year).44 Results of the RELIANCE clinical trial are expected to be relevant to clinicians, payers, and policy makers seeking actionable evidence in COPD from trials embedded in clinical practice.45

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study; the acquisition of the data, data analysis, or interpretation; writing the article and substantial involvement in its revision prior to submission. All authors approved the manuscript submitted for publication.

Other acknowledgements: The statements in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

FDA coauthors reviewed the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and the manuscript for scientific accuracy and clarity of presentation. Representatives of the FDA reviewed a draft of the manuscript for the presence of confidential information and accuracy regarding the statement of any FDA policy. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the FDA.

We also thank members of the independent data and safety monitoring board (A. Sonia Buist, MD, Chair; Donald P. Tashkin, MD; Debra Sellers; Margaret Bate; and Andre Rogatko, PhD), patients with COPD, as well as their caregivers and clinicians, and all study volunteers who served as participants.

Declaration of Interest

All authors received funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute or the Food and Drug Administration. There are no other relevant interests.