Running Head: 25(OH)D Deficiency and COPD Incidence

Funding Support: This study was supported by funding from the Beijing Natural Science Foundation 355 (Shengjie Zhao, 7232165), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Ying Zhu, No. 81700069; Chen Zhu, No. 72573164), the Major Project of Eighth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital (Ying Zhu, No.2021ZD005), the Basic Research Project of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital (Qiang Tong, ynms202408), the 2115 Talent Development Program of China Agricultural University(Chen Zhu), the Pinduoduo-China Agricultural University Research Fund (Chen Zhu, No. PC2024B02011), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation Project (Jianzheng Zhang, No. 7232165).

Date of Acceptance: December 18, 2025 | Published Online Date: January 5, 2026

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D=25-hydroxyvitamin D; BM=body mass; BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence intervals; CHD=coronary heart disease; CKD=chronic kidney disease; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD=cardiovascular disease; DM=diabetes mellitus; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HDL=high density lipoprotein; HR=hazard ratio; ICD-10=International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; IOM=Institute of Medicine; IQR=interquartile range; LDL=low density lipoprotein; OR=odds ratio; RCTs=randomized controlled trials; sCa=serum calcium; SD=standard deviation

Citation: Zhu Y, Zhao S, Zhu C, Zhang J, Tong Q. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency elevates the risk of COPD incidence and mortality: a large population-based prospective cohort study. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2026; 13(1): 59-72. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0638

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (343KB)

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), characterized by progressive airflow obstruction, ranks as the third leading cause of death globally, affecting over 300 million people and imposing a substantial socioeconomic burden.1 Traditional modifiable risk factors, such as tobacco smoke exposure, indoor and outdoor air pollution, and low body mass index (BMI), contribute to its onset, but emerging evidence implicates nutritional deficiencies, including vitamin D, in the disease pathogenesis.2,3 Vitamin D, primarily measured as serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), plays a critical role in immunomodulation and anti-inflammatory processes, potentially mitigating respiratory inflammation central to COPD.4-5 Given COPD's preventable nature, identifying modifiable factors like low 25(OH)D levels could enable targeted interventions to reduce incidence and improve outcomes in high-risk populations.

25(OH)D deficiency is a pervasive public health issue, with European surveys reporting 25(OH)D levels below 50 nmol/L in 40.4% and below 30nmol/L in 13.0% of the general population.6 In COPD patients, deficiency prevalence reaches 40%–70%, raising questions about whether it precedes and exacerbates the disease or arises as a consequence.7 Low 25(OH)D impairs lung epithelial integrity and promotes chronic inflammation, aligning with COPD's pathophysiology.8,9 Cross-sectional studies often show inverse associations, but causality remains debated due to reverse causation risks, such as reduced outdoor activity in symptomatic patients limiting sun exposure, a key vitamin D source.10,11 Epidemiologic evidence on 25(OH)D and COPD incidence is inconsistent.12-15 A meta-analysis of 18 studies (8 cohorts, 5 case-controls, and 5 randomized controlled trials [RCTs]) found no overall link between low 25(OH)D and COPD susceptibility.16 In contrast, another pooling of 21 studies (n=4818 COPD cases) reported a protective effect of higher 25(OH)D.17 Heterogeneity likely stems from variable assays, supplement use, and unadjusted confounders like latitude or BMI. Prospective designs are needed to clarify these discrepancies and inform whether 25(OH)D screening could identify at-risk individuals.

Beyond incidence, low 25(OH)D associates with heightened COPD mortality and comorbidities, complicating management. An L-shaped curve links 25(OH)D <50nmol/L to elevated all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, particularly in individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM).18,19 Prior studies consistently identify common comorbidities in COPD, such as cancer (40%–70%), hypertension (17%–65%), depression (20%–60%), CVD (20%–48%), and DM (10%–45%), which are associated with increased mortality.20-25 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cirrhosis disrupt 25(OH)D metabolism, leading to deficiency rates of 40.7%–85.7% across CKD stages 3–5 and 93% in cirrhosis, respectively.22,26

In COPD cohorts, comorbid depression poses significant challenges for identification and treatment, as its symptoms often overlap with those of COPD itself.27 Among COPD patients, depression exacerbates physical disability, impairs quality of life, increases health care service utilization, promotes noncompliance with medical therapy, and elevates mortality risk.28 Vitamin D deficiency has been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression through mechanisms such as neuroinflammation and serotonin dysregulation, while higher serum 25(OH)D levels and supplementation show potential benefits in mitigating depressive symptoms and reducing its development.29,30 These interconnections highlight the need for further exploration of 25(OH)D's role in modulating depression-related outcomes in COPD patients, as investigated in the present study.

This study addresses these gaps using U.K. Biobank data. Primary objectives were to evaluate 25(OH)D levels and COPD prevalence in a cross-sectional study, and to examine associations with COPD incidence and mortality over 15 years in a prospective cohort. Additionally, subgroup analyses examined effect heterogeneity across demographics, nutrient supplements, and comorbidities to inform personalized strategies.

Method

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

Cross-Sectional Study

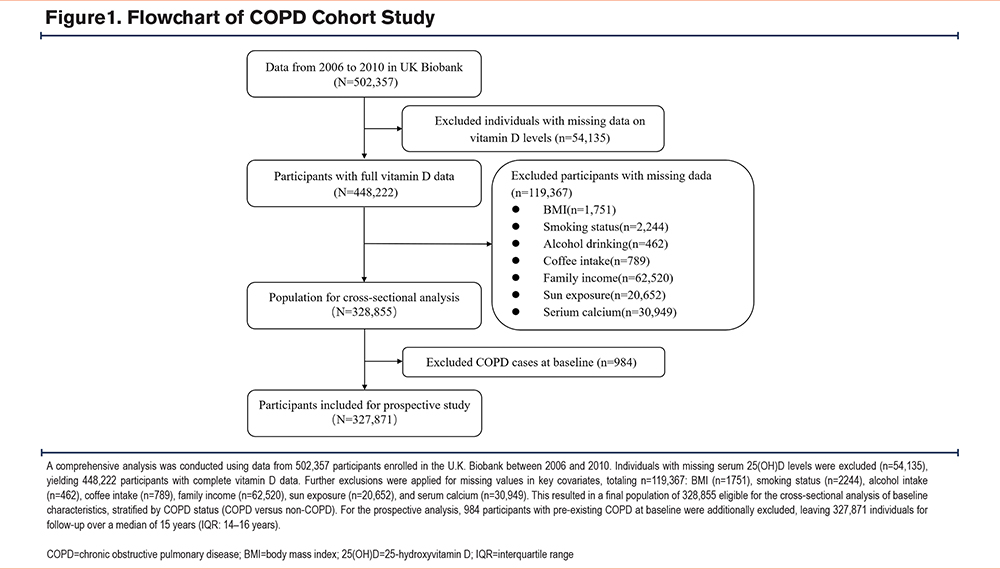

Participants were selected from the U.K. Biobank, a large-scale cohort study initiated between 2006 and 2010. This resource provides comprehensive genetic, lifestyle, environmental, and health-related data for 502,357 individuals aged 37–73 years old recruited across England. The original U.K. Biobank study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all participants provided written informed consent. For our cross-sectional analysis, we included 448,222 participants with complete data on 25(OH)D. After excluding those with missing data on body mass index (BMI; n=1751), smoking status (n=2244), alcohol consumption (n=462), coffee intake (n=789), family income (n=62,520), sun exposure (n=20,652), and serum calcium (n=30,949), a final sample of 328,855 individuals was available for analysis. Among the participants, 13,890 were diagnosed with COPD, while 314,965 were without the disease (Table S1 in the online supplement).

Longitudinal Follow-Up

For the prospective analysis, we excluded 984 participants with a baseline diagnosis of COPD (prior to enrollment), yielding a cohort of 327,871 individuals without COPD (Figure 1). During the follow-up period, 12,906 individuals developed COPD, and 1591 died from this disease by the end of the follow-up (Table 1 and Table S2 in the online supplement). This cohort was followed to assess the risk of incident COPD and COPD-related mortality.

Definitions

25-Hydroxyvitamin D Status Definitions

The quantification of 25(OH)D status was ascertained through the measurement of serum 25(OH)D concentrations, utilizing chemiluminescence immunoassay techniques facilitated by the DiaSorin Ltd LIASON XL instrument.31 We classified vitamin D status using 2 established criteria, as follows:

Institute of Medicine (IOM) Cutoffs32:

- Normal (Sufficiency): ≥50nmol/L

- Insufficiency: 30–50nmol/L

- Deficiency: <30nmol/L

Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline33:

- Normal (Sufficiency): ≥30ng/mL (≥75nmol/L)

- Insufficiency: 21–29ng/mL (50–75nmol/L)

- Deficiency: <20ng/mL (<50nmol/L)

Assessment of COPD With International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision Codes

The definition of COPD from the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), 2024 Report is the presence of nonfully reversible airflow obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity<0.7 postbronchodilation) measured by spirometry.34 We extracted data on events and mortality specifically associated with COPD using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). As J40–J43 primarily encompass patients with chronic bronchitis and emphysema, who may not meet the spirometric criteria for COPD, these were excluded. Ultimately, we selected patients with ICD-10 code J44, which includes the following subcategories of COPD:

- J44.0 (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute lower respiratory infection);

- J44.1 (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute exacerbation, unspecified);

- J44.8 (other specified chronic obstructive pulmonary disease);

- J44.9 (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, unspecified).

Pre-Existing COPD Definition

Pre-existing COPD was defined as a J44 diagnosis recorded prior to study enrollment (baseline date). This was determined by comparing the timestamp of the first COPD diagnosis code against the enrollment date for each participant. Individuals with a pre-enrollment diagnosis were classified as having pre-existing COPD and were excluded from the prospective incidence analysis to minimize immortal time bias (Figure 1).

COPD-Specific Death Ascertainment

Furthermore, COPD-specific deaths were ascertained from the linked U.K. Biobank death register data (Category 10093) using ICD-10 codes J44 (J44.0–J44.9) as the underlying or contributing cause of death.

Covariates

We included certain factors that influence both the exposure (vitamin D status) and outcome (COPD prevalence/incidence/mortality) to minimize confounding as covariates. Specifically, we used 5 sociodemographic factors (age, sex, ethnicity, area [rural or urban], and family income), 6 lifestyles (BMI, smoking, alcohol, coffee, vitamin D supplement, and time spent outdoors in summer and in winter), 5 blood factors (serum calcium [sCa] and 4 kinds of lipids [triglycerides, cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) and high density lipoprotein (HDL)]), and 7 major comorbidities prevalent in COPD that may influence long-term mortality and vitamin D metabolism (hypertension, CVD, CKD, DM, cancer, cirrhosis, and depression).

Socioeconomic variables (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity, residence, income) were included as established COPD risk adjusters, which adjusted for these in vitamin D-COPD analyses.34 Lifestyle factors (e.g., BMI, smoking, alcohol, coffee) reflect modifiable COPD triggers and 25(OH)D influencers.34,35 For vitamin D metabolism, we incorporated supplementation, sun exposure, sCa, and lipids, given their roles in synthesis/regulation.36-38 Comorbidities were selected based on their bidirectional links to both low 25(OH)D and COPD mortality (e.g., CKD/cirrhosis impair 25(OH)D activation; hypertension/diabetes/coronary heart disease [CHD]/cancer/depression amplify systemic inflammation).20-26

Given that older adults are more susceptible to developing COPD, we stratified participants into 2 age groups: those younger than 65 years and those aged 65 years or older. As a baseline for adequate 25(OH)D production, it is noted that direct sunlight exposure for merely 15 minutes twice a week suffices; thus, we defined sun exposure of less than 0.5 hours per day as minimal outdoor activity. Participants were also categorized into 6 household income subgroups. sCa levels were classified into 3 groups: low (<2.2mmol/L), normal (2.2–2.75mmol/L), and high (>2.75mmol/L). BMIs were divided into 4 categories: Underweight (BMI<18.5kg/m2), Normal (18.5–25kg/m2), Overweight (25–30kg/m2), and Obesity (≥30kg/m2).

Statistical Analyses

For all descriptive statistics, continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations and categorical variables were presented as frequencies. To examine the group differences in baseline characteristics, an analysis of Student’s t tests (or Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon tests) was used for continuous variables where appropriate and the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association between categorized serum 25(OH)D levels and COPD prevalence. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression assessed the association between serum 25(OH)D levels and the incidence and mortality of total COPD events, adjusting for potential confounders. Additionally, Kaplan-Meier curves were estimated to depict event-free survival across different 25(OH)D categories, and the log-rank test was employed to compare differences between these curves. Nonadjusted hazard ratios and adjusted hazard ratios, along with their 95% confidence interval (CI), are reported. Additionally, we performed stratified analyses based on 25(OH)D supplement use (yes/no), sex (male/female), age (≥65 years versus <65 years), smoking status (never/previous/current), and statistically significant comorbidities (present/absent) in the fully adjusted model. A likelihood ratio test was performed to assess potential effect modification between 25(OH)D concentrations and stratification variables by comparing models with and without interaction terms.

Our analytical strategy employed a series of nested, progressively adjusted models to systematically control for potential confounders in examining the association between 25(OH)D status and COPD outcomes. Model 1 provided the unadjusted (crude) estimates. Model 2 adjusted for demographic factors (age, sex, ethnicity, area of residence [rural or urban], and family income). Model 3 incorporated additional factors related to lifestyle and dietary habits. (BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, coffee intake, sCa, sun exposure, vitamin D supplementation, and lipids [triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL, and HDL]). Finally, Model 4 represented the fully adjusted analysis, including all clinically justified covariates plus comorbidities (hypertension, CVD, CKD, DM, cancer, cirrhosis, and depression). All primary results are based on Model 4.

Our statistical analyses utilized IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0; Armonk, New York), with forest plots created through GraphPad Prism (version 9.0). Significance was assigned to p-values below 0.05, adhering to rigorous hypothesis testing standards and ensuring statistical integrity with 2-sided tests.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

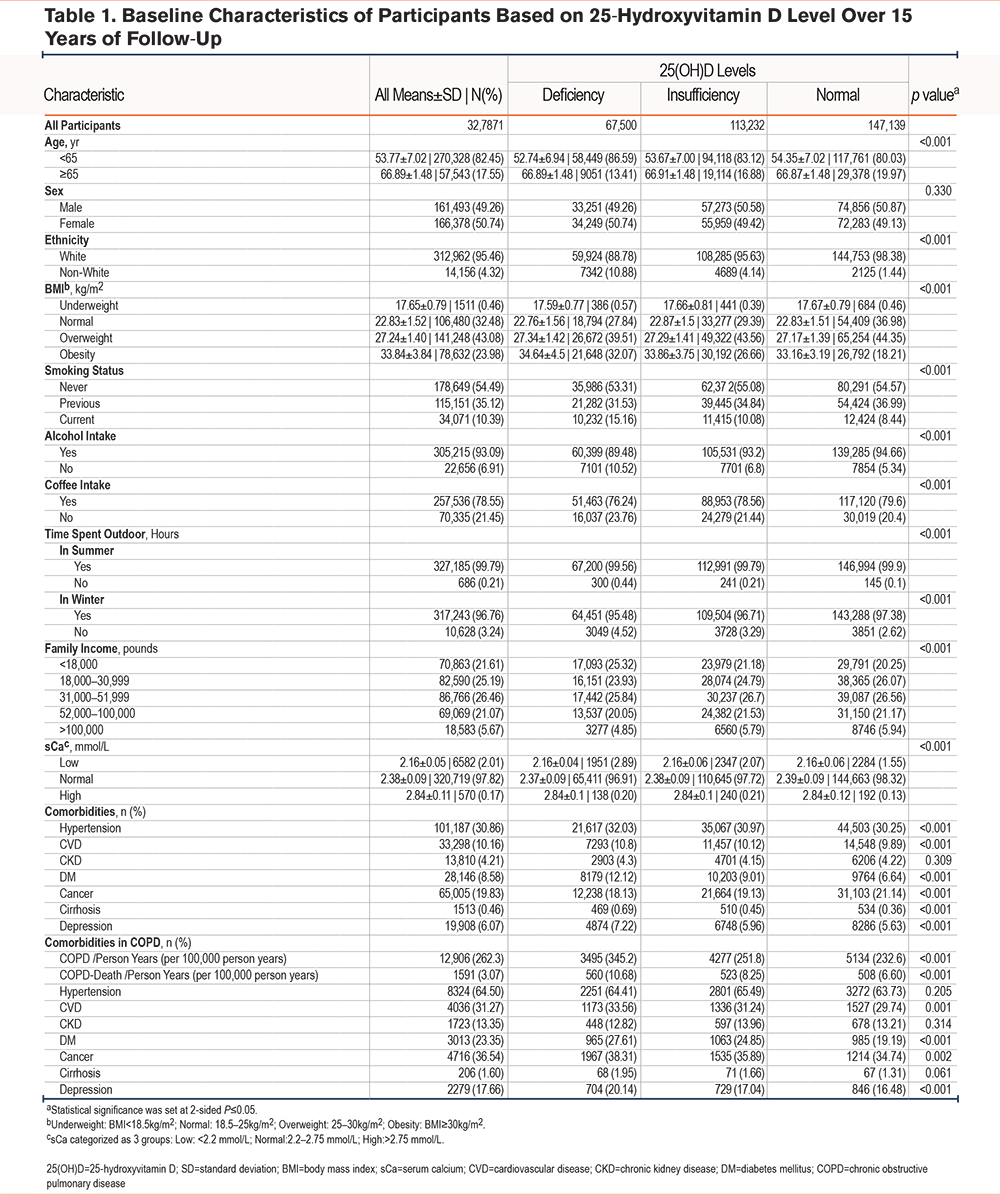

The demographics and baseline characteristics of the cross-sectional study data are summarized in Table S1 in the online supplement. The mean serum 25(OH)D level in COPD patients (45.79±21.78nmol/L) was lower than in healthy controls (48.91±21.00nmol/L). Additionally, 25(OH)D deficiency was observed in 27.3% of COPD patients, compared to 20.32% in the healthy population (Table S1 in the online supplement). Over a 15-year median follow-up period in a cohort of 327,871 participants (Table 1), the overall COPD incidence was 262.3 per 10,000 person years, with higher rates among those with 25(OH)D deficiency (345.2 per 100,000 person years) or insufficiency (251.8) compared to normal levels (232.6) (p<0.001). Furthermore, COPD-specific mortality rates were also observed as higher in participants with 25(OH)D deficiency (10.68 per 100,000 person years than in those with normal levels (6.6 per 100,000 person years). Additionally, the mortality rates among COPD patients with comorbid DM (27.61% versus 19.19%), CHD (33.56% versus 29.74%), cancer (38.31% versus 34.74%), and depression (20.14% versus 16.48%) were significantly higher in the deficiency group. These findings indicate a significant association between 25(OH)D status and COPD outcomes.

Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Association Between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations and COPD Prevalence

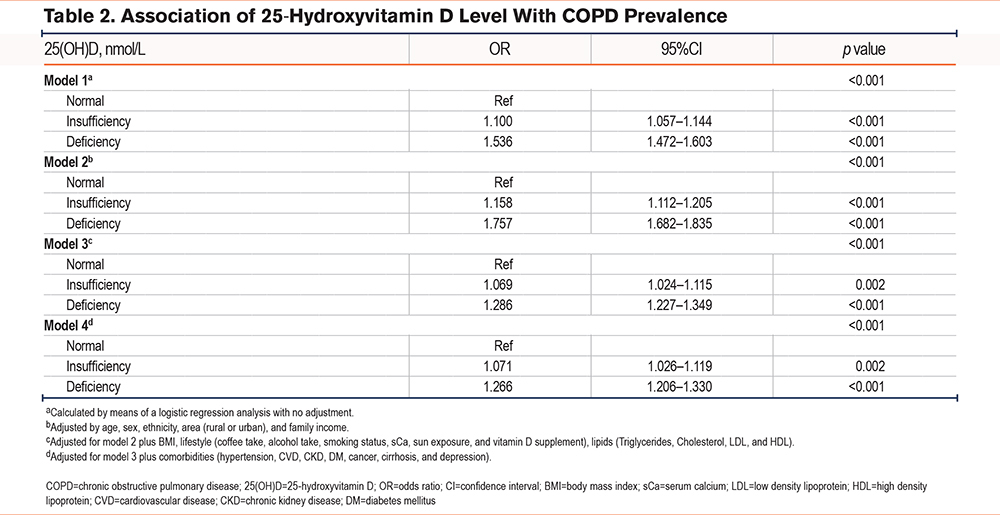

Table 2 summarizes the association between serum 25(OH)D levels and COPD prevalence, analyzed via logistic regression across 4 different models. Compared to normal 25(OH)D levels, both insufficient and deficient categories showed higher odds of COPD in a dose-dependent manner, with associations strengthening for deficiency. In the fully adjusted Model 4, odds ratios (ORs) remained significant at 1.071 (95% CI: 1.026–1.119, p=0.002) for 25(OH)D insufficiency and 1.266 (95% CI: 1.206–1.330, p<0.001) for 25(OH)D deficiency. Consistent with the Endocrine Society diagnostic criteria, our analysis confirmed a significant link between 25(OH)D deficiency and elevated COPD prevalence (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.169; 95% CI: 1.097–1.245) (Table S3 in the online supplement).

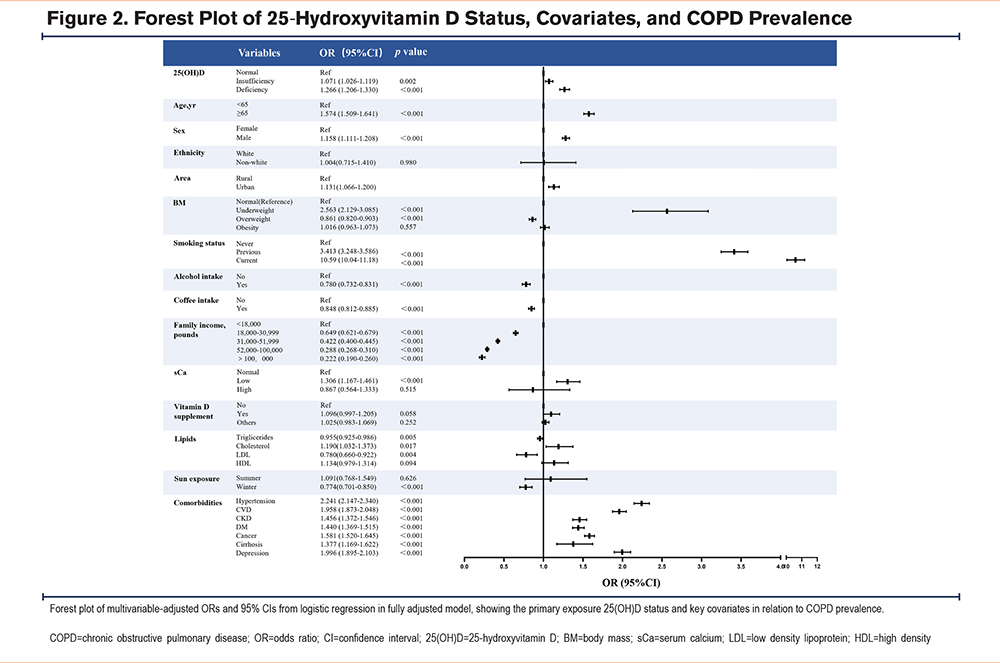

Figure 2 presents a forest plot illustrating the multivariable-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for the associations between various covariates and COPD prevalence from logistic regression analysis (fully adjusted Model 4). In addition to the association between 25(OH)D status and COPD prevalence, other notable associations included advanced age (≥65 years), male sex, urban residence, current-smoking status, and comorbidities such as hypertension and depression, while overweight status showed a protective effect.

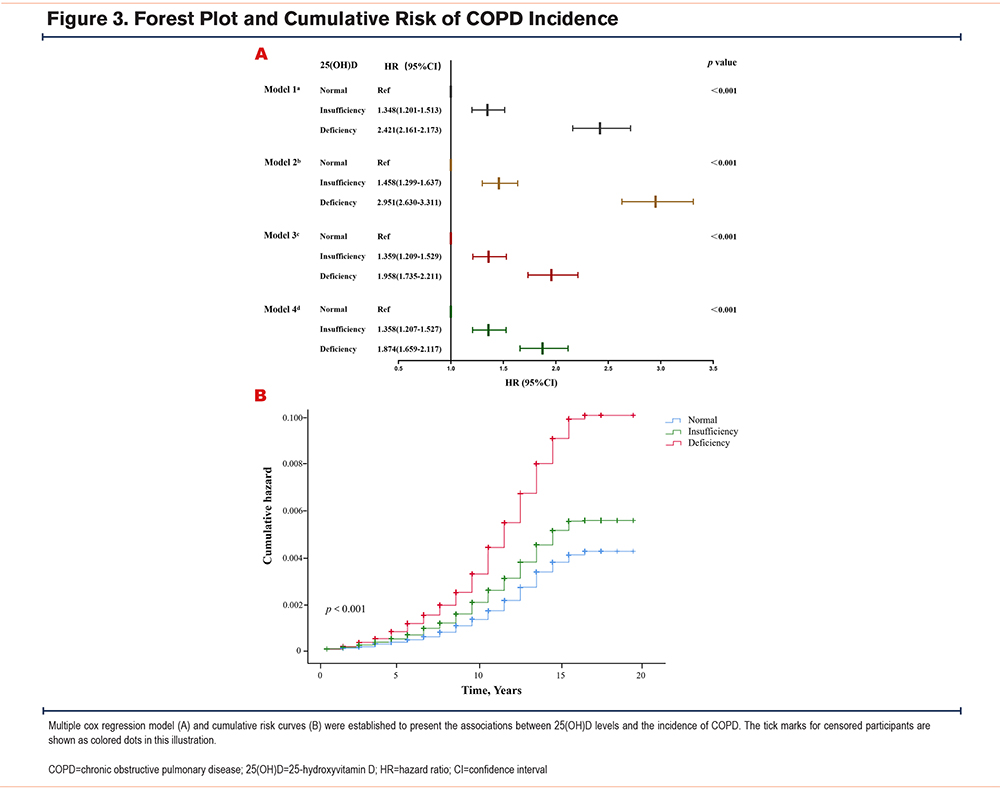

Longitudinal Association of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels With COPD Incidence and COPD-Specific Death

During a median follow-up of 15 (interquartile range [IQR]:14–16) years, 12,906 cases of COPD were recorded in this prospective cohort study (Table S2 in the online supplement). In the fully adjusted Model 4, compared to the normal group, the 25(OH)D deficiency and insufficiency groups exhibited an 87.4% (HR: 1.874; 95% CI: 1.659–2.117) and 35.8% (HR: 1.358; 95% CI: 1.207–1.527) increased risk of COPD incidence, respectively (Figure 3). According to the categorization in the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, similar results were observed in the 25(OH)D deficiency group (HR: 1.724; 95% CI: 1.442–2.062) (Table S4 in the online supplement).

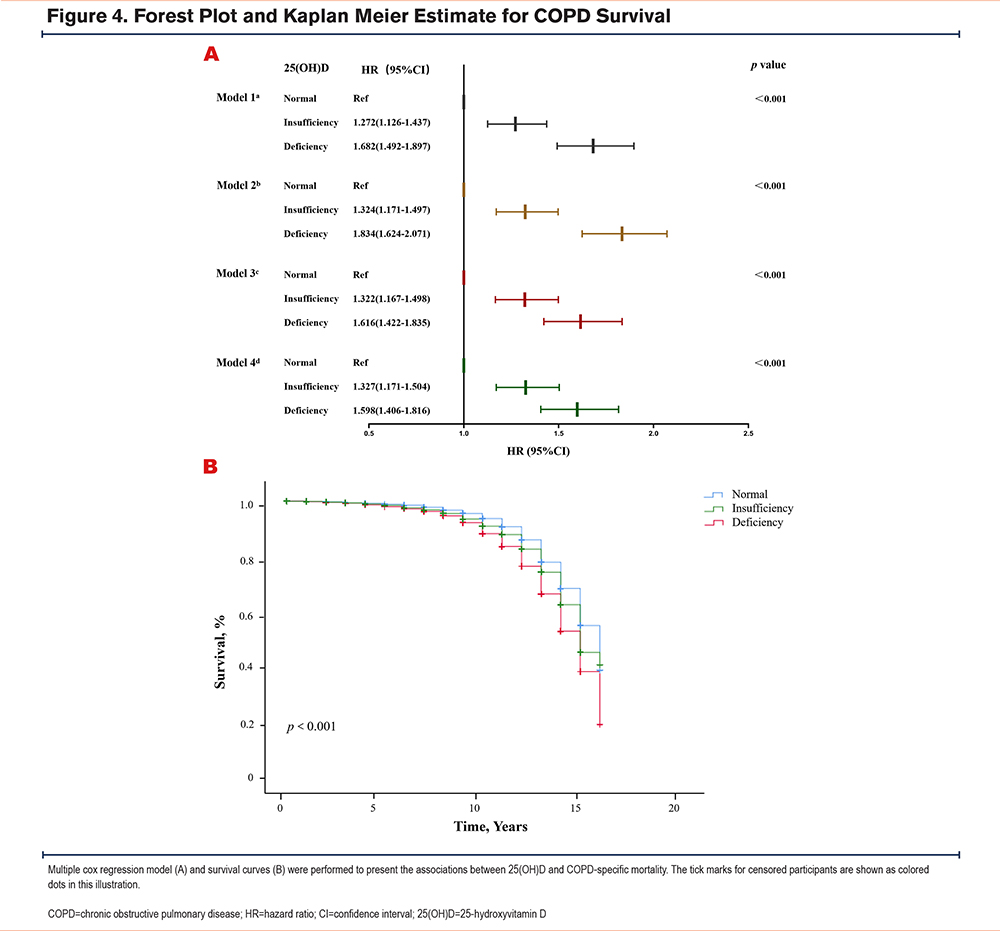

Multivariable analysis across 4 different adjusted models demonstrated a dose-dependent association between serum 25(OH)D status and COPD-specific mortality. Compared to the sufficient group, fully adjusted models revealed a graded elevation in risk, with 25(OH)D-deficient individuals exhibiting a 59.8% increase (HR:1.598, 95% CI:1.406–1.816) and insufficient individuals showing a 32.7% higher risk (HR:1.327, 95% CI:1.171–1.504), as depicted in Figure 4A. Survival probability curves in Figure 4B further supported these findings, with the deficient group exhibiting significantly reduced survival over follow-up (log-rank p<0.001). Stratification by the Endocrine Society criteria similarly confirmed these trends, with complete methodological details (HR: 1.654; 95% CI: 1.366–2.004) in Table S4 in the online supplement.

Subgroup Analysis

COPD prevalence and specific mortality show a stronger association with male gender, advanced age, and smokers [26494423, 37497381]. This aligns with our findings in Figure 2. Consequently, we conducted additional subgroup analyses (Tables S5 and S6 in the online supplement), stratified by gender, age, smoking status, and vitamin D supplementation, to clarify the associations between 25(OH)D levels and risks across these groups. 25(OH)D deficiency was more strongly associated with COPD incidence in men, current smokers, and those not taking vitamin D supplements (p for interaction <0.05). Male gender also played a significant role in the link between 25(OH)D deficiency and COPD mortality risk. COPD comorbidities such as DM, CVD, cancer, and depression showed significant differences between the 25(OH)D deficiency and normal groups. Therefore, we conducted subgroup analyses for these comorbidities. The results showed that the depression subgroup indicates a stronger effect of 25(OH)D deficiency on increasing COPD mortality risk among patients with depression (p for interaction <0.05) (Table S7 in the online supplement).

Discussion

In our cross-sectional study, we utilized a large sample from the U.K. Biobank and identified an association between 25(OH)D deficiency and a higher prevalence of COPD. Specifically, we observed that compared to individuals with normal 25(OH)D levels, those in the deficiency group had a 26.6% increased prevalence of COPD. Subsequently, we designed a prospective study to evaluate the association between 25(OH)D deficiency and the risk of COPD incidence and survival. In our fully adjusted model, the group with 25(OH)D deficiency exhibited a substantially higher COPD incidence (HR[95CI%)]:1.874[1.659–2.117]) and comorbidity (HR[95CI%]:1.598[1.406–1.816]) compared to the control group. Subgroup analyses revealed stronger associations with COPD incidence among men, current smokers, and individuals not taking vitamin D supplements, as well as an increased COPD mortality risk among patients with depression (p for interaction <0.05).

25(OH)D insufficiency and deficiency exhibit substantial variability across diverse demographic groups, including differences in age, sex, and malnutrition or malabsorption, as well as environmental factors such as seasonal variations in sunlight exposure and geographic latitude.39 In our study, the prevalence of reduced 25(OH)D levels was 60.57% among individuals with COPD and 54.91% among those without COPD, which is consistent with prior research40-42 reporting rates ranging from 8.7% to 69%. In the cross-sectional study, the overall prevalence of COPD was 4.25% (13,890/328,855), which is lower than the 10.3% reported in the GOLD 2024 guidelines, but higher than the 2.7% prevalence rate reported in the 2021 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study report.43 Still, several factors explain the lower baseline COPD rate compared to population estimates:

- Case definition specificity: Our narrow ICD-10 J44.x criteria excluded chronic bronchitis and emphysema without spirometric confirmation, enhancing specificity but reducing prevalence.

- Cohort smoking profile: The U.K. Biobank's ~89% never- and former-smokers yield a lower COPD burden than in higher-smoking populations.

- Healthy volunteer bias: Participants are healthier and of higher socioeconomic status, likely lowering prevalence and attenuating effects.

During a median follow-up of 15 (IQR:14–16) years, the overall COPD incidence was 262.3 per 10,000 person years, which is highly consistent with prior U.K. Biobank analyses using similar definitions and follow-up lengths.35 Thus, the longitudinal disease occurrence in our cohort is not unusually low. These rates fall largely within the range of reported global age-standardized incidence rates,44 which averaged 197.37 per 100,000 people worldwide and reached the highest in Nepal (310.58).

Our study showed the HR of 25(OH)D deficiency was 1.27 for COPD risk, which aligned with previous studies35,45,46ranging from 1.23 to 2.00. A large cohort of 18,507 participants followed for over 20 years confirmed a prospective link between lower 25(OH)D and an elevated COPD risk, but was limited to White individuals in low-sun-exposure areas and delayed 25(OH)D measurements.45 Similarly, Zhu et al analyzed U.K. Biobank data, finding that the lowest 25(OH)D quintile(<31.7nmol/L) conferred a 23% higher COPD risk (HR:1.23, 95% CI:1.15–1.32) compared to the fourth quintile.35 Our findings align with Zhu et al in associating lower 25(OH)D with higher COPD incidence and meaningfully extend prior findings:

- Clinically actionable 25(OH)D thresholds: Unlike population-based quintiles, we used IOM and the Endocrine Society cutoffs to distinguish insufficiency and deficiency, facilitating direct clinical application in screening, supplementation, and risk stratification.

- Complementary cross-sectional and prospective analyses: To resolve prior cross-sectional inconsistencies, we combined prevalence and incidence assessments, linking 25(OH)D <50nmol/L to higher COPD onset and worse survival for a more comprehensive temporal view.

- Specific COPD case definition: We restricted cases to ICD-10 J44.0–J44.9, excluding chronic bronchitis and emphysema codes that may lack diagnostic confirmation, thereby minimizing misclassification and bolstering association validity.

- Comprehensive confounder and comorbidity adjustment: We adjusted for expanded factors affecting vitamin D and COPD (e.g., sun exposure, supplementation, lipids, CKD, cirrhosis, depression), with associations remaining stable in sensitivity analyses.

- Mortality analysis stratified by comorbidities: We advanced prior studies by evaluating COPD survival in comorbid subgroups, highlighting depression as a mortality modifier and identifying a high-risk group overlooked previously (p for interaction <0.05).

We further elucidated the impact of 25(OH)D on COPD survival. Participants with insufficiency and deficiency faced 32.7% (HR,1.33; 95 CI%,1.17–1.50) and 59.8% (HR,1.60; 95 CI%,1.41–1.82) higher COPD-specific mortality risks, respectively, versus normal levels. U.K. Biobank data indicated higher 25(OH)D reduced all-cause (17%), CVD (23%), and cancer (11%) mortality, though COPD-specific effects were unexamined.47 Zhu et al reported a 38% higher risk overall for COPD death in the lowest quintile.35 COPD comorbidities independently elevate death risk.48-50 Our models comprehensively adjusted for these factors, revealing persistent associations, including an increased COPD mortality risk among depressed patients (p for interaction <0.05). This finding is consistent with evidence of higher mortality among COPD patients with depression.51,52

The association between 25(OH)D levels and COPD outcomes may be underestimated or overestimated when using quintiles. To address this, we employed both the U.S. IOM and Endocrine Society criteria to assess 25(OH)D status and identify deficiency. Our findings consistently show that 25(OH)D deficiency and insufficiency (per IOM cut-offs) or deficiency alone (per Endocrine Society guidelines) increase risks of COPD incidence and mortality.32,33 These aligned results suggest that 25(OH)D levels below 50nmol/L are a significant risk factor for both COPD risk and survival.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, participants were younger than in prior studies, potentially limiting generalizability, as younger cohorts may have distinct risk profiles and disease trajectories compared to older, more COPD-prone groups. Future research should span broader age ranges to capture life-stage variations. Second, the prospective analysis lacked symptom scores and lung function data for COPD patients, restricting insights into 25(OH)D’s effects on clinical outcomes and severity. Since severe cases comprised only 0.8% of events, 25(OH)D deficiency linked more to mild-to-moderate but not severe COPD incidence. Further research should examine the role of 25(OH)D across severity levels. Third, subgroup analysis by vitamin D supplementation (used by only 3.9% of participants) showed significant association between 25(OH)D deficiency/insufficiency and COPD incidence in those not taking it. This small sample precludes firm conclusions on supplementation's protective effects. Intervention trials, such as RCTs, are needed to test causality and efficacy. Fourth, season variations strongly influence 25(OH)D levels (particularly in the U.K.), but our dataset lacked measurement of season data, hindering adjustments. Future studies should account for seasonality to improve accuracy. Fifth, the prospective study excluded baseline COPD patients to confirm vitamin D deficiency's link to increased COPD risk. Future research should be conducted to assess potential reverse causality. Overall, these limitations underscore the value of more robust, comprehensive studies to address these gaps. Nonetheless, our work offers preliminary insights into the 25(OH)D-COPD relationship.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest a higher prevalence of 25(OH)D deficiency among individuals with COPD compared to those with insufficiency and sufficiency. Using 2 criteria to assess 25(OH)D status, we observed potential associations between levels below 50nmol/L and elevated risks of COPD incidence and specific mortality. Depression comorbidity showed strong association with mortality risk. These results warrant cautious interpretation; future research, including large-scale RCTs, is needed to evaluate supplementation efficacy and causal links.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: ZY and TQ conceptualized the manuscript. ZY and ZSJ were in charge of the funding acquisition. ZSJ contributed to the methodology. ZY and ZC were responsible for the formal analysis. ZC contributed to the data curation. ZY and ZC were in charge of the investigation and methodology. ZY and TQ were responsible for project administration. ZY and ZSJ were in charge of the software. ZY and ZSJ wrote the original draft. ZJZ and TQ were responsible for resources and supervision. TQ contributed to the visualization. ZJZ was responsible for the validation. ZY, ZJZ, and TQ were responsible for reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials: All data are publicly available in the U.K. Biobank repository (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

Other acknowledgments: Our thanks to all the study participants and the anonymous editors and reviewers for their constructive feedback, which has significantly enhanced the quality of this publication.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.