Running Head: Lung Cancer in COPD

Funding Support: None

Date of Acceptance: December 16, 2025 | Published Online Date: January 6, 2026

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HR=hazard ratio; IQR=interquartile range; NSCLC=nonsmall cell lung cancer; OR=odds ratio; SBRT=stereotactic body radiation therapy; SD=standard deviation; VATS=video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

Citation: Tardif A, LeBlanc C, Roy P, et al. Lung cancer in patients with COPD: predictors of surgery and long-term survival following lung resection. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2026; 13(1): 29-38. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0643

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of mortality by cancer with approximately 1.8 million deaths in 2022 surpassing colorectal, pancreatic, and breast cancer combined.1,2 Surgery for stage 1 and 2 non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) is still the treatment of choice,3 although advances in radio-oncology with the development of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) offering the possibility of delivering a high dose of radiation in a targeted area is now considered a viable option for many patients unfit for surgery.4 Although local control may be similar between surgical resection and SBRT, survival is more favorable with the former treatment even when the analysis is limited to patients with operable disease,4,5 perhaps with the exception of T1N0M0 (early stage) disease in which long-term survival may be achieved with both therapies.4

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is found in 50% to 70% of the lung cancer population,6 smoking being the main shared risk factor for both pathologies,7 but COPD also represents an independent risk factor for lung cancer.8 COPD is often the main reason for not performing surgery,9 lung function being recognized as a predictor of mortality and morbidity following lung resection,10 particularly in those with moderate or severe airflow limitation.11 A conservative practice toward patients with COPD may be justified considering that higher mortality and morbidity rates have been reported in this situation, particularly if patients were to die of their comorbid conditions and not of lung cancer. However, in one study involving 4069 patients with stage 1 lung cancer, including 449 treated by SBRT and 3620 by surgical resection, the latter treatment was associated with decreased lung cancer-related death in all scenarios of severity of airflow limitation.12

We recently reported our experience with lung resection for lung cancer in patients with COPD.13 Although 30-day mortality was slightly higher in patients with COPD compared to those with normal lung function (1.3% compared to 0.2%), the mortality rate was within the expected range for this type of surgery.10 This study mainly involved patients with mild to moderate airflow limitation contributing to favorable postoperative outcomes. Alternatively, favorable mortality rates after lung resection in COPD could be related to applying strict and conservative selection criteria before proposing surgery. One downside of using stringent selection criteria for surgery is the possibility to deny the best treatment option to marginal patients who could nevertheless tolerate lung resection

COPD is often not the sole comorbid condition as it is frequently associated with advanced age and cardiovascular disease.14-16 The role of accumulating comorbidities in the treatment decision regarding the treatment of lung cancer in patients with COPD is unclear. Many studies report that lung cancer resection is the best therapeutic approach,4,17,18 but it may not always be the case.19-23 Secondary analyses of retrospective studies support the view that surgery is advantageous in the majority of clinical situations,12 but these results were obtained in a heterogeneous population in which COPD was not universally present and in which the impact of added comorbid conditions, in addition to COPD, was not addressed. It would be of interest to evaluate the efficacy of surgical compared to nonsurgical approaches exclusively in patients with COPD who are affected or not by other comorbid conditions.

Accordingly, the objectives of this study were to: (1) compare the characteristics of patients with COPD who underwent surgical resection for early-stage NSCLC compared to a nonsurgical approach; (2) describe the predictors of lung resection in this population; (3) evaluate the impact of surgery on long-term survival; and (4) determine the mortality causes in this population.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective study of patients who were diagnosed with resectable (stage 1 and 2) NSCLC and treated at the Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec, a tertiary-care hospital and main thoracic oncology center in eastern Québec, Canada between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2019. Data about patients who underwent lung resection was prospectively collected in the institutional biobank database after written consent was obtained. Data on patients who did not have surgery was collected in a clinical database of medically treated patients with lung cancer in our institution. The study was approved by the institutional ethic committee (project CER 21184).

To be included in this study, patients needed to be 18 years old or older and have an airflow limitation caused by COPD as defined by a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio < 0.70 in the presence of a smoking history of at least 10 pack years. Spirometry was done according to published guidelines.24 Airflow limitation was stratified according to the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria.25 Patients were included at the first occurrence of lung cancer. Patients were excluded if they had no spirometry available, normal lung function on pulmonary testing, or abnormal spirometry not caused by COPD. They were also excluded if they had stage 3 or 4 lung cancer at diagnosis or if the final histologic pathology showed any other histopathology than NSCLC.

Patients were evaluated by a pulmonologist with specific training in lung oncology and/or a thoracic surgeon who considered medical history, comorbidities, functional status, respiratory function tests, disease extent, feasibility of complete surgical resection, as well as the individual’s preferences in order to reach a therapeutic decision. In our center, the lung oncology group works as a team in such a way that investigation and therapeutic decisions are practically standardized. Nevertheless, no therapeutic algorithm was used to determine operability and final decision relied on the integration of the clinical and paraclinical data and a clinician’s judgment in conjunction with the patient’s input. We run a weekly tumor board, but stage 1 and 2 lung cancer cases are generally not presented when the therapeutic decision is straightforward, although individual cases could be discussed at the request of the treating physician to reach a decision. Treatment offered included surgical resection (most commonly through video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery [VATS] and including lymph node dissection and sampling), SBRT (4–5 fractions, 48–50 grays), conventional radiotherapy (20–30 fractions, 50–60 grays), or therapeutic abstention. SBRT became available in 2010, but patients had to travel to another region; it has been available in our area since 2014, facilitating access to therapy.

Data Collection

For patients who underwent lung resection, the following information was extracted from the institutional biobank’s database: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking history, spirometry, extent of lung resection, type of surgery, histopathological diagnosis, and pathologic TNM staging based on staging criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 8th edition.26 Two authors (AT, CLeBlanc) also reviewed medical files to confirm the diagnosis of COPD and to collect information on comorbidities, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, renal insufficiency, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. We also collected information about medication including the use of beta-blockers, antihypertensive, hypolipidemics, oral hypoglycemics, and inhaled therapy including bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids. For the nonsurgical group, the same data was obtained from medical chart review and the clinical database. For these individuals, lung cancer staging was based on clinical TNM, 8th edition.27 Survival status was calculated from the time of surgery, or, for the nonsurgical patients, from the first medical visit for lung cancer, censored on December 31, 2019 from the medical file or from the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec, a provincial organization to which all deaths occurring in the province of Québec are reported. Mortality causes could be obtained for patients treated between 2009 and 2012 from the Institut de la statistique du Québec.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies and were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. To handle the missing data for BMI, smoking status, and renal insufficiency, we used a multiple imputations procedure, in which 100 datasets of plausible values for missing data were imported. A fully conditional specification method using the predictive mean matching technique that assumes the existence of a joint distribution for all variables and ensures that imputed values are plausible was performed for continuous variables. The discriminant function method was used for dichotomous variables. We tested the adequacy of the iterations (convergence) by visual inspection of trace plots for different chains which showed no apparent trends for the imputed values between the imputation models. The imputation procedure and the subsequent analyses were performed according to the Rubin’s protocol. Univariate logistic regressions were performed to determine predictors of surgery. Continuous variables were checked for the assumption of linearity in the logit using graphical representations. It was found that the relationships between age, BMI, FEV1 (percentage predicted), and the odds of having surgical resection were not linear with significant changing risks along the range of these variables. Knots in these relationships were determined using a nonlinear logistic regression model that maximized the likelihood function. Variables with a probability value < 0.20 in the univariate regressions were candidates for the multivariable logistic regression model building. The variable selection was performed using a forward approach. The Akaike's information criterion and Schwarz's Bayesian criterion were used to compare candidate models. After model building, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was performed to assess the goodness-of-fit of the model. The overall survival analysis used the Nelson-Aalen estimator for the survival curve and compared with the log-rank test. A Cox regression statistical model adjusted for the propensity score was performed. The propensity score was defined as the likelihood of undergoing surgery assigned to each patient and was computed from the multivariable logistic regression model. Using the same model-building strategy mentioned previously, the retained variables were age, FEV1, sex, BMI, active smoking status, coronary artery disease, renal failure, peripheral artery disease, FVC, FEV1/FVC, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and lung cancer stage 1B and 2A. Statistical significance was present with a 2-tailed p value < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

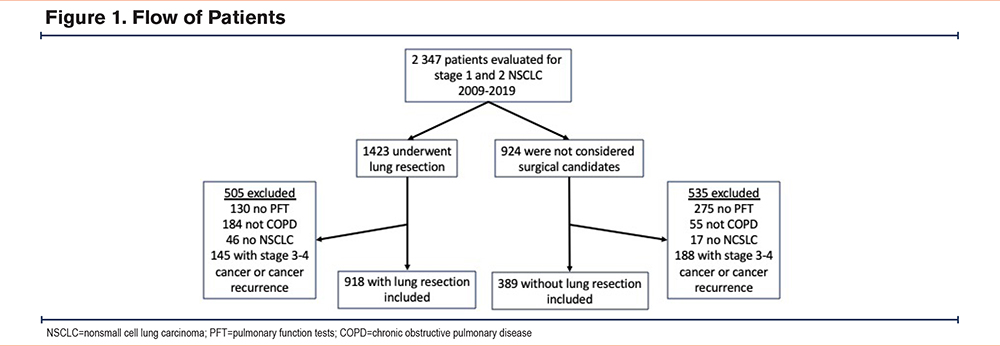

The flow of patients is presented in Figure 1. Between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2019, 2347 patients with COPD were evaluated for NSCLC. From this number, 1423 patients underwent lung resection for stage 1 and 2 NSCLC, including 918 who met the inclusion criteria for this study. VATS was done in 82% of surgical patients. In the same period, 924 patients were not considered as surgical candidates, among whom 389 met the inclusion criteria for this study. The nonsurgical group included patients who underwent SBRT (n=147), conventional external beam radiotherapy (n=86), and therapeutic abstention (n=156). A preference not to receive active therapy was expressed by 22 patients among the 156 patients who did not receive active treatment. For the remaining ones, this therapeutic choice was based on the integration of the clinical and paraclinical information by the clinician. Histologically-proven cancer was documented in all but 68 patients who all belonged to the nonsurgical group.

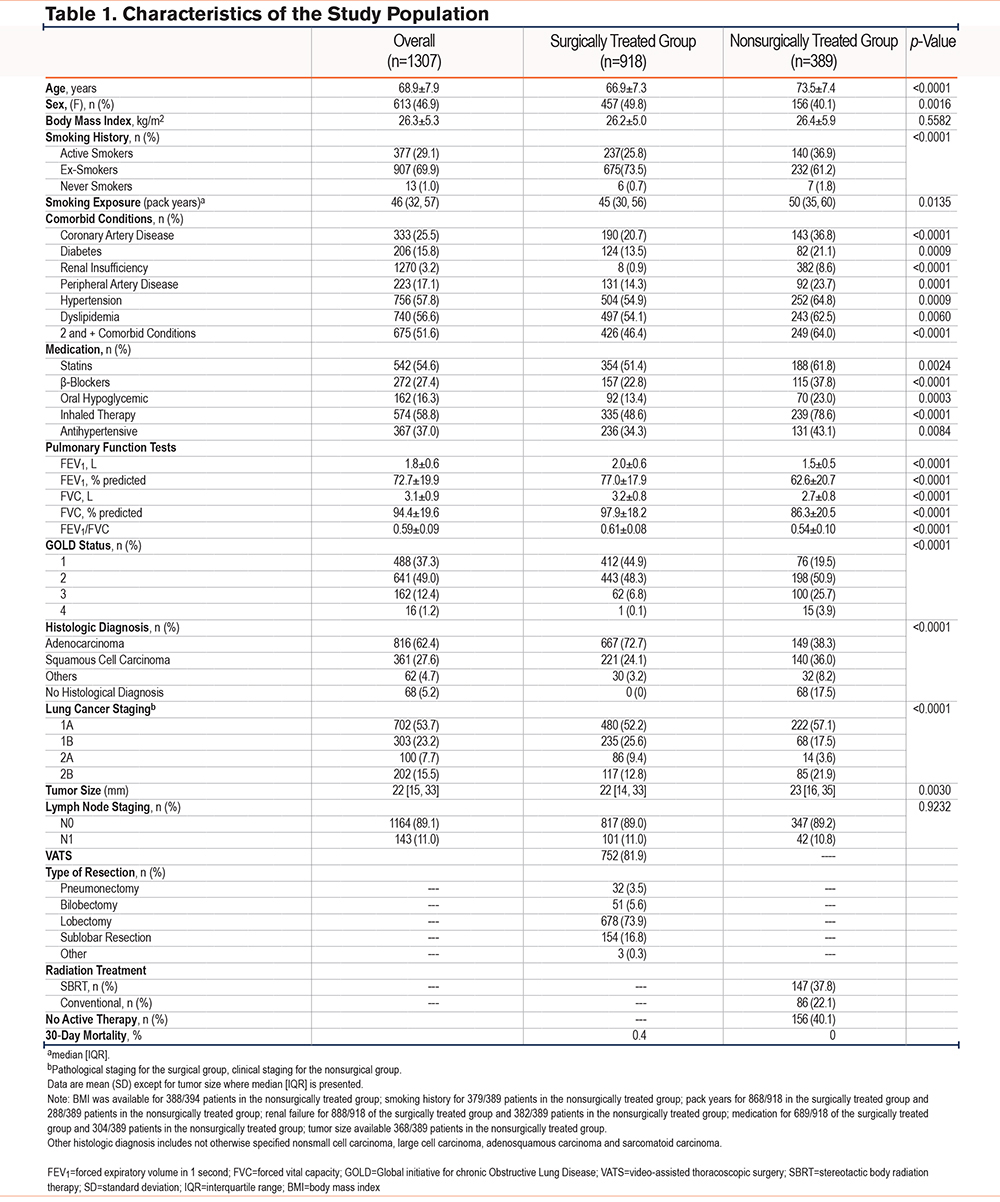

Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. The study population included 613 (47%) women, with a majority being ex-smokers. Mean FEV1 averaged 73 20% predicted value, including 178 patients with GOLD 3+ (FEV1 < 50% predicted). The most frequently encountered lung cancer stage was stage 1A, with a predominance of adenocarcinomas. In comparison to patients in the nonsurgical group, patients who had surgery were younger and the proportion of females was greater. Also, the proportion of current smokers and the prevalence of comorbid conditions were lower than in the nonsurgically treated group. Consistent with this, surgical patients took fewer medications. Patients in the nonsurgical group had a lower FEV1, the proportion of GOLD stage 3 and 4 was larger, and they were more frequently using inhaled medication. There were more adenocarcinomas in the surgically treated group which also had a lower prevalence of stage 2B than in the nonsurgical group. Lymph node status was similar in both groups. The 30-day mortality was 0.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.02 to 1.20%) in the surgical group; no death was recorded during this period in the nonsurgical group.

Predictors of Surgical Treatment

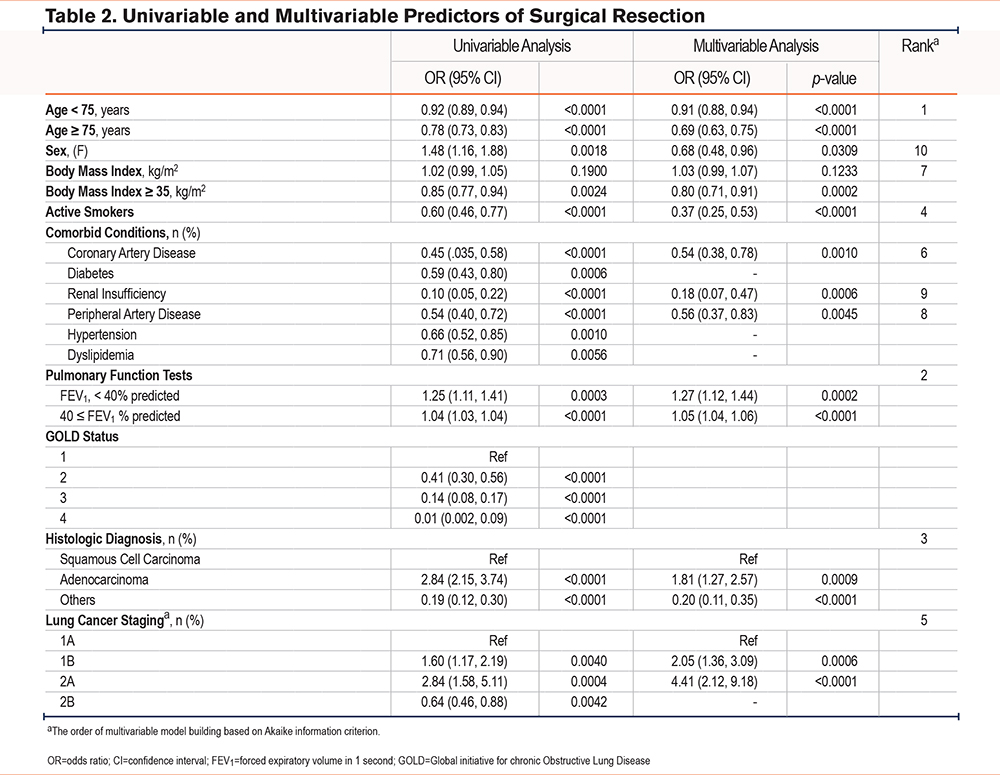

In the univariate analyses, multiple factors were associated with the probability of having surgical treatment, including age, sex, BMI, active smoking, comorbid status, FEV1 (percentage predicted), tumor histology, and stage (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, the main negative predictor of surgery was age, particularly in individuals aged 75 years and older where each 1-year increment in age is associated with a 32% reduction in the odds of having surgery. FEV1 was the second most important factor, notably when less than 40% predicted, where each 1% predicted increase in FEV1 was associated with a 27% increase in the probability of having surgery. At over 40% of predicted, the relationship was weaker, with each 1% predicted increment in FEV1 predicting a 5% increase in the odds of having surgery. Being diagnosed with an adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma (odds ratio [OR]=1.81, 95% CI: 1.27 to 2.57), stage 1B (OR=2.05, 95% CI: 1.36 to 3.09), and stage 2A (OR=4.41, 95% CI: 2.12 to 9.18) were all associated with an increased likelihood of undergoing surgery. In turn, active smoking was a strong factor predicting a nonsurgical approach (OR: 0.39, CI 0.27 to 0.56). The presence of coronary artery disease, BMI above 35 kg/m2, and renal insufficiency were also associated with a nonsurgical approach (ORs ranging from 0.18 to 0.80).

Survival

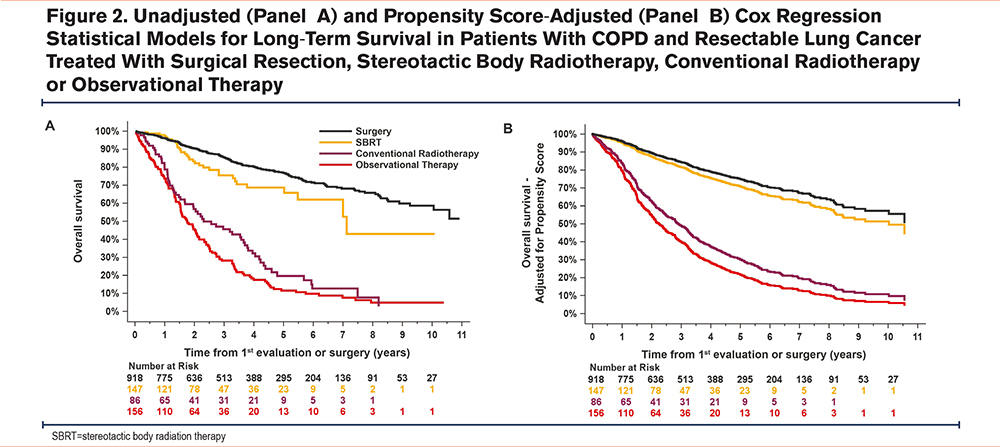

During the follow-up period, 192 patients (21.0%) in the surgically treated group and 229 (58.9%) in the nonsurgically treated group died. Median survival was 2.7 years (95% CI: 2.3 to 3.3 years). Multivariate Cox models for survival are shown in Figure 2. Propensity score-adjusted survival was significantly reduced with therapeutic abstention (hazard ratio [HR]=0.18, 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.25) and conventional radiotherapy (HR=0.24, 95% CI: 0.17 to 0.33) compared to surgically treated individuals. Survival was also reduced in SBRT-treated patients compared to surgically treated patients, but this did not reach statistical significance (HR=0.84, 95% CI: 0.55 to 1.26). Conventional radiotherapy was associated with poorer survival compared to SBRT (HR=0.28, 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.43).

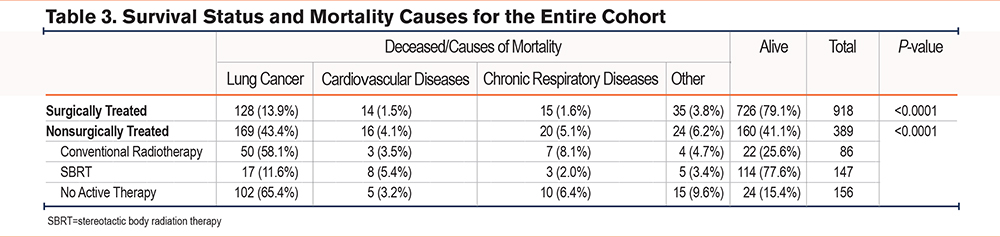

Mortality Causes

The causes of mortality could be ascertained from death certificates for the entire cohort (Table 3). The distribution of mortality causes differed between the 2 groups; excess in mortality due to lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic respiratory diseases were noted in the nonsurgical group compared to surgically treated patients (p=0.001). Exploring the causes of mortality according to each type of nonsurgical treatment revealed an excess lung cancer mortality with conventional radiotherapy and therapeutic abstention but not with SBRT.

Discussion

In this study, patients with COPD undergoing lung resection for resectable lung cancer had superior survival compared to those for whom a nonsurgical therapeutic approach was selected. This observation persisted even after adjusting for confounding by indication with the exception of those who were treated with SBRT for which the numerical advantage of surgery did not reach statistical significance. In the multivariate analysis, age, sex, smoking status, FEV1, BMI, histological diagnosis, and lung cancer stage were predictors of surgical resection. We noted an excess of cancer and noncancer mortality in the nonsurgical group compared to the surgically treated group. Our study contributes to the literature by virtue of its large, well-characterized study population, which includes spirometric confirmation of COPD and the ascertainment of mortality causes in the study population.

Although not a universal finding,19-23 these results are consistent with the general notion that surgical resection is the treatment of choice in early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancer.4,17,18 In the present study, surgery was clearly superior to conventional radiotherapy and therapeutic abstention. When considering the low mortality rate in the surgical group (0.4%), it is possible that expanding the surgical indications to a broader patient population could help improve survival in individuals with COPD who are diagnosed with resectable lung cancer while keeping the postoperative complication rate in an acceptable range. With lung cancer being a leading cause of mortality in COPD,28 selecting the best treatment option for this disease is paramount to optimize survival. The present study provides a strong argument not to refuse lung cancer surgery solely on the presence of COPD, and may also help clinicians to engage in a balanced and informed discussion with patients with COPD regarding the available therapeutic options for lung cancer and their relative risks and benefits.

Like others,12 we found a tendency for better outcomes following surgery versus SBRT. Nevertheless, SBRT is a viable option for high-risk patients, particularly in patients with stage T1N0M0 cancer where there is not a clear survival advantage of one therapy versus the other.4 In our cohort, SBRT also provided a survival advantage compared to conventional radiotherapy, a finding that is concordant with the result of a meta-analysis of 2 randomized trials and 15 cohort studies conducted in stage 1 NSCLC.29

It remains unclear whether less favorable outcomes associated with the nonsurgical approaches are due to cancer progression or complications from severe comorbidities that underlie the decision for no surgery. To address this question, we had access to the mortality causes of the entire cohort (Table 3). We also explored the causes of mortality according to each type of nonsurgical treatment. The results are concordant with an excess lung cancer mortality with conventional radiotherapy and therapeutic abstention but not with SBRT. This observation further reinforces the benefit of lung resection even in patients with a comorbid condition, such as COPD, while supporting the notion that SBRT is an adequate alternative to surgery.

We found older age, particularly above 75 years, being female or a current smoker, having a low FEV1, and having a higher BMI were predictors of medical treatment instead of lung resection. This suggests that these risk factors are integrated by clinicians when therapeutic decisions are made despite the absence of a formal algorithm to guide therapeutic choice. Remarkably, several of these predictors of a nonsurgical approach have been previously identified to also predict major morbidity and mortality following lung resection. For example, a report based on the General Thoracic Surgery Database comprising data from 27,844 lung resections, identified advancing age, current smoking, and low FEV1 as risk factors for postoperative mortality and complications.30 At variance with our findings, being male predicted poor postoperative outcome. Reasons for this discrepancy with our results are uncertain but may be related to the specificity of the present study population which exclusively involved patients with COPD, a disease for which being female is associated with worse outcomes.31 In our study, age, particularly above the age of 75 years, predicted that a conservative approach was often the preferred treatment option. Frailty has been reported to be a better predictor of postoperative mortality following lobectomy than age alone.32 Although not currently systematically done in clinical practice, the integration of several variables in predictive models could help predict more accurately postoperative outcomes in patients who are considered marginal candidates for lung resection.

Limitations

This was a retrospective study done in a single center which may limit the generalizability of the data. Relying on clinical data available in medical charts may have led to some misdiagnoses in individuals in whom airflow limitation is due to other diseases such as asthma. Some variables that are considered relevant to risk stratification before lung surgery, such as diffusion capacity and functional status,30 were not widely available for the medical chart review. Propensity score matching reduces, but does not eliminate, potential unbalance between experimental groups in nonrandomized trials. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the treatment effect of surgery might have been overestimated due to unaccounted confounding variables. It might be surprising that only 60% of patients were treated with inhaled medication despite having COPD. COPD undertreatment is common,33 providing an opportunity to optimize lung function and to reduce postoperative complications,34 possibly allowing more patients to become eligible for surgery. Since this investigation was not done in the context of a research project, no treatment algorithm was proposed to determine which treatment would be offered; we relied on the clinical judgment of pulmonologists and thoracic surgeons, and this might have influenced treatment decisions compared to a pre-established standardized decision tree. Nevertheless, the similarity in the predictors on a nonsurgical approach and the risk factors for postoperative mortality and morbidity supports the adequacy of the clinical decision process. We used the clinical staging for the nonsurgical group rather than the pathologic staging which was applied for the surgical group. This may have led to underestimating tumor burden in the nonsurgical patient in whom positive N1 or N2 node stations, that are occasionally discovered during surgery, could have been missed despite thorough clinical evaluation. The extent of this effect is difficult to quantify, but it may have potentially contributed to more cancer mortality in this group compared to the surgically treated group. Lastly, 156 patients did not receive active treatment, which may appear surprising. The decision to opt for therapeutic abstention was based on the integration of the clinical and paraclinical information by the clinician, while also considering patients’ preferences. Following the introduction of SBRT in our area in 2014, a safer and more effective approach than conventional radiotherapy, there was a progressive decline in the proportion of patients who did not receive active treatment; between 2012 and 2019, we observed a 60% reduction in the number of patients who did not receive active treatment.

Conclusion

Patients with COPD with a resectable NSCLC who did not undergo lung resection had a higher mortality rate compared to those who underwent surgery. The excess cancer-related mortality in nonsurgical patients suggested that lung resection should be considered to improve survival in this population.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the design of the work and to data analysis. AT, CL, PR, MP, ER, GC, EP, MCB, and FM contributed to data acquisition. AT and FM drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved with data interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. FM is accountable for all aspects of the work, on behalf of the co-authors.

Other acknowledgments: The authors thank Christine Racine from the Biobank of our institution for her help in accessing clinical and pathological data.

Declaration of Interest

FM reports grants from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Novartis, and personal fees for serving on speaker bureaus and consultation panels from GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca. He is financially involved with Oxynov, a company which is developing an oxygen delivery system.

All other authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.