Running Head: Cost-Related Nonadherence Effects on COPD Outcomes

Funding Support: This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants U01 HL089897 and U01 HL089856 and by National Institutes of Health contract 75N92023D00011. The COPDGene study (NCT00608764) has also been supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Committee that has included AstraZeneca, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sunovion.

Date of Acceptance: November 12, 2025 | Published Online Date: December 9, 2025

Abbreviations: 6MWD=6-minute walk distance; ADI=area deprivation index; BD=bronchodilator; BODE=Body mass index-airflow Obstruction-Dyspnea-Exercise capacity; CAT=COPD Assessment Test; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COPDGene=COPD Genetic Epidemiology study; CRN=cost-related nonadherence; FEV1=forced expiratory volume over 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; GED=general education development; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HS=high school; ICS=inhaled corticosteroid; IQR=interquartile range; IRR=incidence rate ratio; LABA=long-acting beta agonist; LAMA=long-acting muscarinic antagonist; SD=slope difference; SGRQ=St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

Citation: Suri R, Non A, Bailey J, Conrad D. The long-term effects of cost-related nonadherence on COPD outcomes and progression in the COPDGene study cohort. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2026; 13(1): 1-7. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0689

Online Supplemental Material: Read Online Supplemental Material (203KB)

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has an estimated global prevalence of 10.3%. In the United States alone, COPD is projected to cost over $40 billion per year over the next 20 years.1 Pharmacologic treatment has the potential to improve symptoms and exercise capacity and reduce exacerbations.1 Poor adherence to prescribed medication regimen for all diseases results in increased hospitalization, progression of disease, death, and health care costs.2,3 Nonadherence in COPD due to all causes ranges from 43% to 58.7%, which is associated with increased mortality and hospital admission.4-6

Osterberg et al2 describes the interactions between patients, providers, and the health care system as areas that can negatively affect medication adherence. This includes an understanding of correct medication delivery, overall disease, and treatment benefits as well as access to physicians and the health care system. Additionally, the cost of medications plays an important role and can lead to cost-related nonadherence (CRN). For example, the interaction between patients and the health care system can include frequent switching of formulary, high out-of-pocket medication costs, and poor access to clinics and pharmacies. Additionally, the interaction between providers and the health care system can include poor knowledge of drug costs and of insurance coverage of different formularies.2

Up to one-third of older adults reduce adherence to all medications to limit the burden of cost.3 In COPD, specifically, national health interview survey data suggests 19% of individuals experience cost-related medication nonadherence.7 This issue is further exacerbated by a complex health care system where frequent formulary changes due to cost considerations lead to further nonadherence.8

This study used a large longitudinal observational cohort of adults with COPD to better understand the individual level effects on disease progression of nonadherence specifically due to cost. We hypothesized that cost-related nonadherence would be associated with faster lung function decline, increased exacerbation and symptom burden, and worse health status.

Methods

Study Design

The COPD Genetic Epidemiology (COPDGeneⓇ) study is an observational, multicenter, longitudinal analysis of healthy never-smokers and individuals with ≥ 10 pack-year smoking history with and without COPD. Participants were recruited from 20 different sites across the United States and have completed 3 phases of visits, every 5 years over 15 years. Data collection was conducted in-person and via telephone to complete questionnaires, functional assessment, pulmonary function test, multi-omics assessments, and quantitative chest computed tomography evaluation.9

This secondary analysis evaluated a subset of individuals within COPDGene with spirometry confirmed Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)1 stages 1 to 4 COPD at the baseline visit who completed the social and economic questionnaire at either the phase 2 or 3 visit. This questionnaire was not administered during the phase 1 visit. This resulted in a total of 2521 participants.

An individual was categorized as experiencing CRN if they answered yes to either “in the last year, because of expenses or lack of coverage, have you not filled a prescription” or “in the last year, because of expenses or lack of coverage, have you taken less medication.” Answering no to both questions classified an individual as not experiencing CRN. These questions are similar to those administered by the National Health Interview Survey to evaluate cost-related nonadherence.7 It is important to note that these questions are asking about CRN for any medications and are not specific to COPD-directed therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Individuals were dichotomized as either experiencing CRN or not experiencing CRN. Baseline characteristics including demographic variables, smoking status and pack years, functional status, symptom burden, and health status were compared using chi-squared tests for categorical variables or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables.

Linear regression models were used to assess associations of CRN with the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD),10 the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score,11 the Body mass index-airflow Obstruction-Dyspnea-Exercise capacity (BODE) index12 at visit 1 and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT)13 at visit 2, which is the first visit in which this questionnaire is used. Exacerbation history was obtained at each of the 3 visits by asking frequency of exacerbations in the prior 12 months before the visit. To evaluate exacerbation history, a mixed effect negative binomial model was used with the total follow-up time as an offset.

Longitudinal analyses were performed using a mixed-effects linear regression model with site, participant random intercept, and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) random slope to evaluate the association of experiencing CRN with FEV1, both in liters and calculated as percentage predicted. Additional longitudinal analyses were conducted evaluating the association of experiencing CRN with the 6MWD, the SGRQ score, the BODE index, and the CAT Score.

Covariate Selection

The models controlled for age, gender, race, smoking status defined as current and former smokers, pack-year smoking history, baseline FEV1, and prior history of asthma. Complete case analysis was used for all models. The national area deprivation index (ADI) is a neighborhood ranking based on education, employment, housing quality, and income.14,15 Due to significant missing ADI data in 190 participants, this was not included in the primary analysis. A sensitivity analysis was performed with ADI as a covariate to evaluate for any change in association.

Stata version 18 software (StataCorp; College Station, Texas) was used for the analysis. COPDGene was approved by the institutional review board at each site and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

There were 2740 participants who had baseline COPD and returned for a subsequent visit. Of those, 2523 participants completed the social and economic questionnaire at either visit 2 or 3. Differences between the groups having completed the questionnaire are shown in e-Table 1 in the online supplement. The group that did not complete the questionnaire was older, had lower FEV1, and experienced worse overall health status as defined by the SGRQ. Of the remaining 2523, there were 2 additional participants who had missing data and were omitted from the analysis. Of the remaining 2521 participants, 408 (16.2%) had reported experiencing CRN. At the time of reporting CRN, 93.5% of participants endorsed having health insurance. Of those with insurance, 86% had Medicare or private insurance, 11% had Medicaid, 2% had military insurance, and 1% were unsure of their insurance type.

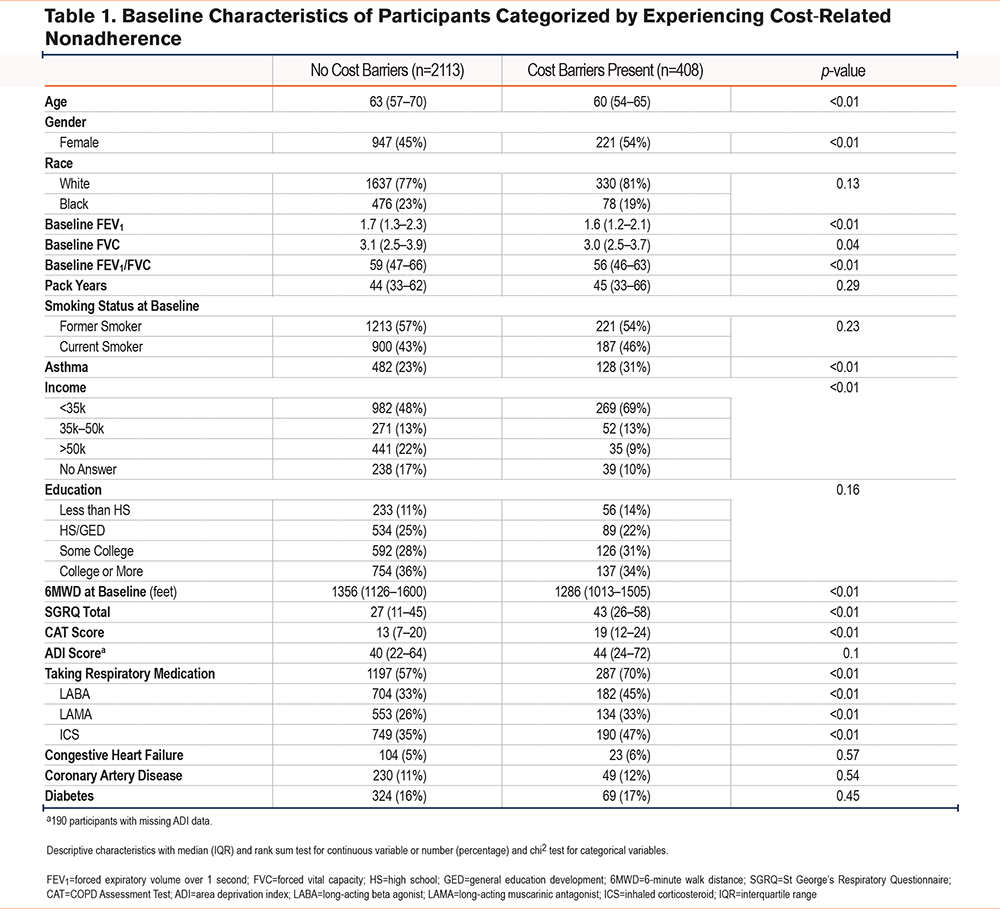

Individuals experiencing CRN were younger, more likely to be female, and had worse lung function on spirometry. They had lower income but no significant difference with regards to race, baseline smoking status, pack-year history, education level, ADI, or comorbidities. Individuals experiencing CRN had a shorter 6MWD and a worse SGRQ, CAT Score, and BODE index (Table 1).

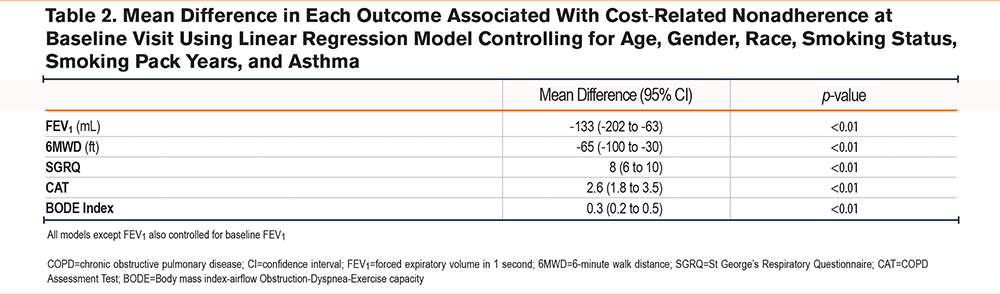

After controlling for relevant confounders in a multivariable analysis, experiencing CRN was associated with a reduced FEV1 of -133mL (95% confidence interval [CI]: -202 to -63mL) and a shorter 6MWD by a mean of 65 feet (95% CI: 30 to 100 feet). CRN was also associated with an increased reported symptom burden as evidenced by a higher CAT score by 2.6 points (95% CI: 1.8 to 3.5) and a worse health status by SGRQ (+8 points [95% CI: 6 to 10]), which is higher than the minimum clinically important difference for the CAT Score and the SGRQ of 2 and 4 respectively.16,17 Additionally, there was an association of an increased BODE index by 0.3 (95% CI: 0.2 to 0.5) (Table 2). There was no difference in magnitude of effect or significance level when controlling for ADI in the models (e-Table 1 in the online supplement).

Longitudinal Analysis

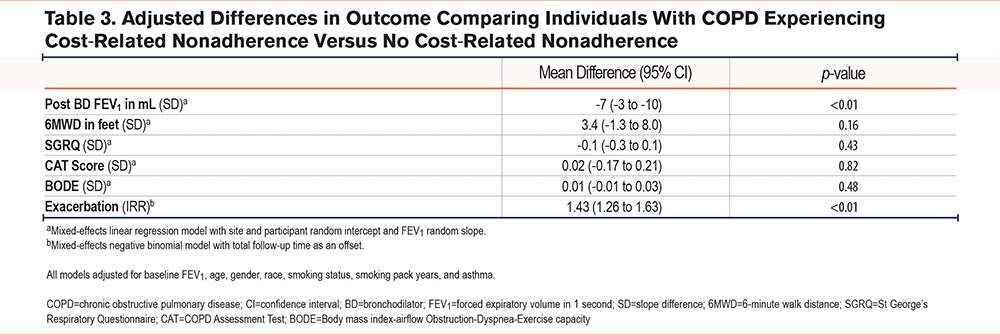

In longitudinal analysis using mixed-effects models and controlling for relevant confounders, experiencing CRN was associated with a faster lung function decline. Specifically, individuals without CRN had a lung function decline of 38mL per year while those with CRN had a decline of 45mL per year, equating to a faster decline of 7mL per year (95% CI: 3mL to 10mL) in those with CRN (Table 3).

Similarly, individuals without CRN had a decline in FEV1 to forced vital capacity of 0.3% per year while experiencing CRN was associated with a decline of 0.5%, an additional 0.2% per year (95% CI: 0.1% to 0.3%). Additionally, CRN was associated with increased rates of exacerbation with an incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.43 (1.26 to 1.63).

Despite these differences in longitudinal outcomes, there was no difference observed in the rate of change in the 6MWD, the SGRQ, the CAT score, or the BODE index. Importantly, there was no difference in magnitude or significance when controlling for ADI in any of the models (e-Tables 2 and 3 in the online supplement).

Discussion

Prior literature has focused on all-cause medication nonadherence and associations with COPD-related outcomes.4-6 Our analysis is novel and significantly adds to the discussion by focusing on an important type of nonadherence due to medication cost, in a large well-profiled cohort of adults with COPD, therefore highlighting a potential targetable policy to improve compliance and COPD outcomes.

This analysis provides several significant findings. In this cohort, over 90% of individuals experiencing CRN had health insurance, suggesting the problem goes beyond simply insurance status. Experiencing CRN is associated with worse lung function by spirometry, higher symptom burden, worse health status, and higher mortality risk by the BODE index. The magnitude of mean difference in these associations is especially notable and clinically significant with an SGRQ of +8, a CAT of +2.6, and an FEV1 of -133mL. Longitudinal analysis in this well-profiled cohort further highlights the relationship of CRN and COPD outcomes by demonstrating an association of an increased rate of FEV1 decline and a higher IRR for experiencing a COPD exacerbation.

There are many factors that contribute to CRN. The pharmaceutical industry in the United States functions outside of the free market, which requires a fully informed consumer with an understanding of cost and benefit and free market entry for sellers.18 The consumer, in this case the patient, is not fully informed as they rely on recommendations from physicians, who may not be aware of out-of-pocket costs incurred by each patient.2,18 Insurance formulary and pharmacy benefit managers also influence the prescribed medication.8 Additionally, the market itself allows for a temporary monopoly through patents.19 As a result of these factors, drug prices in the United States are higher than other countries.18

According to prior claims data analysis, respiratory medications experience high price elasticity compared to other classes of medications. Increases in out-of-pocket costs for respiratory medications associates with a significant reduction in utilization.20 In a real-world experiment performed in a Medicare Advantage population, reducing out-of-pocket copays increased the proportion of days covered by approximately 15%, which equated to a 55% relative increase compared to the control group. In this study, individuals in the deductible phase saw copay reductions from over $400 to $10 or less.21

Cost-sharing models, with the intent of reducing health care overutilization, is a tool designed to reign in overall costs. Specifically, pharmaceutical expenditures are significantly reduced with even small increases in copayment.22 However, these tools are indiscriminatory in that there is an inability to differentiate between restricting overutilization versus restricting necessary medical treatment.

As our study highlights, CRN is associated with faster lung function decline and higher rates of COPD exacerbation, which may in turn increase total health care expenditures. COPD exacerbations have previously been shown to be a significant contributor to the total cost of COPD care.1 The cost-sharing model may not be appropriate or cost-effective for a disease with significant prevalence and a high mortality rate such as COPD.

Cost sharing for airway diseases is further complicated by limited generic options, which are typically cheaper. Patent regulations have allowed for prolonged exclusive rights through techniques such as patents on the device and device hopping without having a medication with a new mechanism of action.19 Higher costs of brand name drugs combined with high price-elasticity for respiratory medications and cost-sharing payment models can significantly contribute to CRN.

The Inflation Reduction Act passed by Congress in 2022 allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate certain drug prices. The first round of 10 medications is estimated to save Medicare $6 billion dollars yearly and save beneficiaries an additional $1.5 billion.23 This program, in addition to the $2000 out-of-pocket cap, is a significant step in the right direction to reducing overall cost-related nonadherence. The first round of medications selected did not include any respiratory medications targeting COPD. The second round, which would go into effect in 2027 and is currently undergoing negotiation, does include 2 respiratory inhalers. Including inhaler medications targeting COPD to reduce CRN could be beneficial to individuals with COPD.

This analysis has several limitations. The definition of CRN in this analysis is narrow compared to other definitions in the literature, which also ask about skipping medications or delaying refills due to cost.7 There were differences in baseline characteristics for those who completed the questionnaire, which may introduce bias, as those who completed the questionnaire were younger and had healthier lung function, indicating we may be underestimating effects of CRN. For those who completed the questionnaire, information regarding cost-related nonadherence and exacerbations is subject to recall bias and was not specific to COPD-related medications. Specifically, one could theorize a potential recall bias, such that individuals with faster lung function decline may be more likely to report cost-related barriers, as greater symptom burden could enhance their awareness and recollection of obstacles to optimal outcomes. Additionally, the questions for nonadherence were only asked at visits 2 and 3 and asked retrospectively for the preceding 12 months. This analysis does not include granular data on participant insurance, copays, frequency of missed doses, or other types of nonadherence that are unrelated to cost but may still contribute to outcomes. The cohort study design also does not account for unmeasured confounders and limits the potential for causal inference. An example of an unmeasured confounder is ambient pollution exposure which is associated with worse COPD outcomes and is also associated with individuals experiencing lower socioeconomic status and subsequently CRN.

Despite these limitations, this analysis has significant strengths. COPDGene is a well profiled and relatively large cohort study of Black and White adults with 15 years of longitudinal follow-up that specifically inquired about social determinants of health. Additionally, outcome assessments included not only subjective measurements such as the CAT questionnaire but also objective measurements such as the 6MWD, exacerbations, and spirometry.

Conclusion

Cost-related nonadherence is associated with increased symptom burden, worse health status, faster lung function decline, and increased exacerbations. Policy changes to reduce medication costs may reduce cost-related nonadherence to COPD medications, reduce decline in lung function, and presumably lead to long-term cost-savings for the health care system. Future negotiation of drug prices should include medications targeting COPD.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: RS, AN, JB, and DC conceptualized the manuscript. RS and AN contributed to the methodology. RS was in charge of the formal analysis and writing the original draft. RS, AN, JB, and DC contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript submitted for publication.

Declaration of Interest

RS and DC participated in an advisory board for Verona. AN and JB have nothing to declare.