Running Head: COPD Exacerbations and Quality of Life

Funding Support: This work was supported by IIR 14-060 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development Service.

Date of Acceptance: December 19, 2025 | Published Online Date: January 5, 2026

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; CCI=Charlson Comorbidity Index; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRQ=Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1%pred=FEV1 percentage predicted; HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HRQoL=health-related quality of life; mMRC=modified Medical Research Council; OR=odds ratio; RSQ=Response to Symptoms Questionnaire; SD=standard deviation; VA=Veterans Affairs

Citation: Wang N, Locke ER, Simpson T, et al. The impact of treated and untreated COPD exacerbations on long-term health-related quality of life. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2026; 13(1): 49-58. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0665

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the 5th leading cause of death in the United States and incurs annual medical costs of $24 billion among adults age 45 and older.1 COPD exacerbations, episodes of worse breathing symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, or sputum production, are a major source of morbidity for patients.2-4 Increased exacerbation frequency, severity, and duration contribute to decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL).5-8

Patients do not always seek immediate medical care for COPD exacerbations. Many patients delay their presentation to medical care, or never seek medical care at all, during an exacerbation.2,5-9 An estimated 50% of exacerbations go untreated.2,10 Untreated exacerbations are known to have similar short-term effects compared with treated exacerbations, which may include acute changes in lung function11 and diminished health status and HRQoL.12-14 However, there is limited understanding of the impact of untreated exacerbations on long-term morbidity and quality of life. One prospective cohort study conducted in China found that patients who had any unreported COPD exacerbations had significantly worse HRQoL at 1 year compared to patients who did not have exacerbations.15

Furthermore, there is incomplete understanding of the differences in characteristics between untreated and treated exacerbations. Studies in alpha-1 antitrypsin disease, a genetic COPD variant, showed that untreated exacerbations tend to have fewer symptoms and shorter duration as compared to exacerbations where patients sought treatment.16 In those without alpha-1 antitrypsin, one study found that unreported exacerbations are associated with fewer symptoms than reported exacerbations.15

The aim of this study is to expand upon existing research by examining the differences in characteristics between untreated and treated exacerbations and by better understanding the impact of untreated COPD exacerbations on long-term HRQoL.

Methods

A secondary analysis was performed using data from a prospective observational cohort study of 410 veterans with COPD, conducted at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System in Washington State and the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System in Colorado. Eligibility criteria included COPD diagnosis, postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity ratio of < 0.7, at least 1 treated COPD exacerbation in the preceding year, and enrollment in a VA primary care or pulmonary clinic. Exclusion criteria included life expectancy < 1 year, diagnosis of dementia, or residence in a nursing facility. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at both institutions.

Participants attended an intake visit where they completed baseline lung function via spirometry and comprehensive questionnaires including medical history, dyspnea level measured with the modified Medical Research Council dyspnea (mMRC) score, self-reported comorbidities measured with the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),17,18 and current depression and anxiety symptoms measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).19 HRQoL was measured using the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) that comprises 20 questions summarized into 4 domains: dyspnea, fatigue, emotional function, and mastery. Each CRQ domain has a range from 1–7 (higher scores indicate better HRQoL), with a minimally clinically important difference of 0.5 for each domain.20-22

During the 1-year follow-up period, an automated interactive voice response service called participants every 2 weeks to screen for COPD exacerbations. If positive, trained research staff called participants to complete detailed questionnaires assessing the number and type of symptoms present, the severity of symptoms, the perceived cause of the exacerbation, and whether participants had contact with medical providers or health care utilization. Exacerbations were defined by new or worsening respiratory symptoms lasting at least 48 hours. The onset of exacerbations was measured from the day the new or worsening symptoms were present. The study utilized a modified version of the Response to Symptoms Questionnaire (RSQ), a questionnaire based on the Self-Regulation Model of Illness to assess how cognitive and emotional factors influence the decision to seek care.23,24 RSQ has previously been used in studies of patients seeking care for ischemic stroke,25 acute myocardial infarction,26,27 and heart failure exacerbations.28 The RSQ was modified for patients with COPD to examine the cognitive and emotional factors that influenced the decision to seek care. The RSQ includes a question on how “bothersome” participants’ symptoms were, which was used to help measure the participant’s sense of the severity of the exacerbation, as well as questions to assess the emotional (anxiety) and cognitive (seriousness and control over symptoms) response to the exacerbation.

Exacerbations were considered treated if participants took systemic glucocorticoids, antibiotics, or both.2,3 Most often, participants were prescribed these medications at the time of their exacerbation, although some had a supply on hand and self-initiated treatment. The total duration of the exacerbation in days was calculated from onset to when participants reported their symptoms had recovered to baseline. Participants with persistent, stable, and unresolved respiratory symptoms present at the end of 6 weeks after exacerbation onset were considered to have reached a new baseline, and the exacerbation was considered completed at that time. The CRQ was repeated for participants at the end of the 12-month study period.

Statistical Analysis

To examine baseline characteristics, participants were categorized into mutually exclusive groups based on the types of exacerbations they experienced during the follow-up period: no exacerbations, one or more untreated exacerbation, one or more treated exacerbation, and mixed treated and untreated exacerbations. Continuous variables were compared for each exacerbation category using linear regression, and categorical variables were compared using chi-squared analyses.

To compare characteristics of untreated versus treated exacerbations, 2-level mixed-effects logistic regression models were used to estimate differences between exacerbation characteristics, including exacerbation severity (measured using the RSQ), different symptoms present, number of symptoms, and self-reported cause of exacerbation. The predictor was the type of exacerbation (treated or untreated) with random effects at the participant level.

To examine the association between treated and untreated COPD exacerbations and long-term HRQoL scores measured by the CRQ, 2 related approaches were taken. First, the total number of treated and untreated exacerbations were entered into the model as separate variables in a linear regression model to predict changes in CRQ at 12 months. Second, logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio of a decrease in CRQ scores of 0.5 (the minimum clinically important difference) or greater at 12 months for each additional untreated or treated exacerbation. Both models adjusted for baseline CRQ and potential confounders including age, gender, FEV1 percentage predicted (FEV1 %pred), baseline dyspnea (mMRC), comorbidities (CCI), HADS-depression and HADS-anxiety scores, and the number of self-reported exacerbations in the prior year. These covariates were selected as potential confounder variables based on existing literature.2,9,13-15,19 All analyses were conducted using Stata 17.0 (StataCorp, LLC; College Station, Texas).

Results

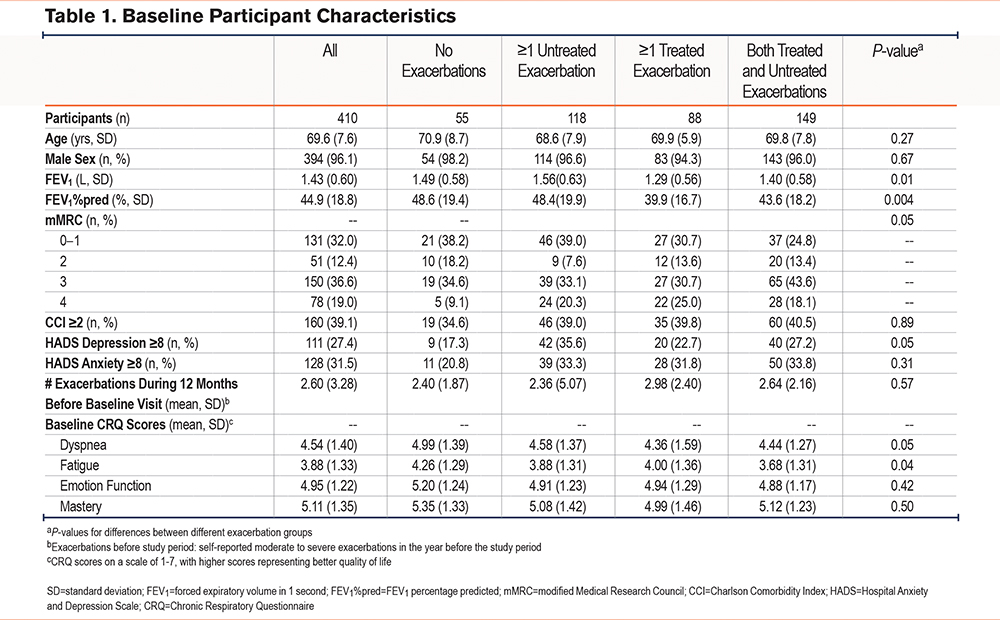

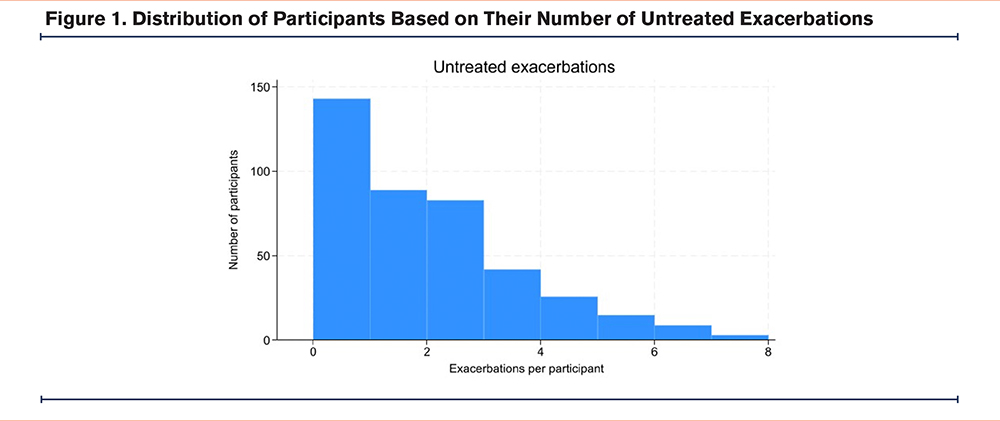

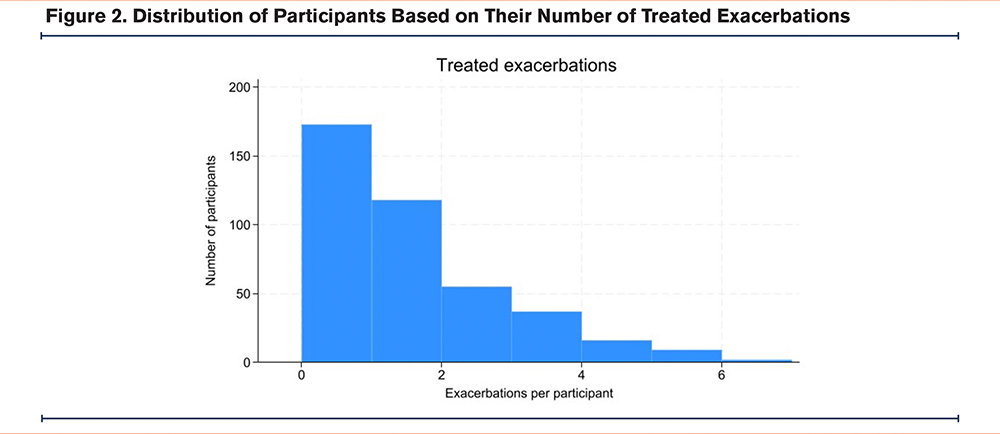

A total of 410 participants enrolled in the study. Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 69.6 (standard deviation [SD] 7.6) and 394 (96%) were male. The mean FEV1 was 1.43L (SD 0.60), mean FEV1%pred was 44.8% (SD 18.8%), and participants had an average of 2.60 self-reported exacerbations in the year before the baseline visit. Over 12 months, 355 of the participants (86.6%) experienced a total of 1097 exacerbations, of which 460 (42%) were treated (Figures 1 and 2).

Baseline characteristics of participants in each exacerbation category are shown in Table 1. There were differences in baseline FEV1, FEV1%pred, mMRC, HADS depression scores, and baseline CRQ dyspnea and fatigue domain scores between the different groups (Table 1). The average number of untreated and treated exacerbations experienced by each participant in the mixed exacerbation group was similar: 2.39 untreated exacerbations and 1.87 treated exacerbations.

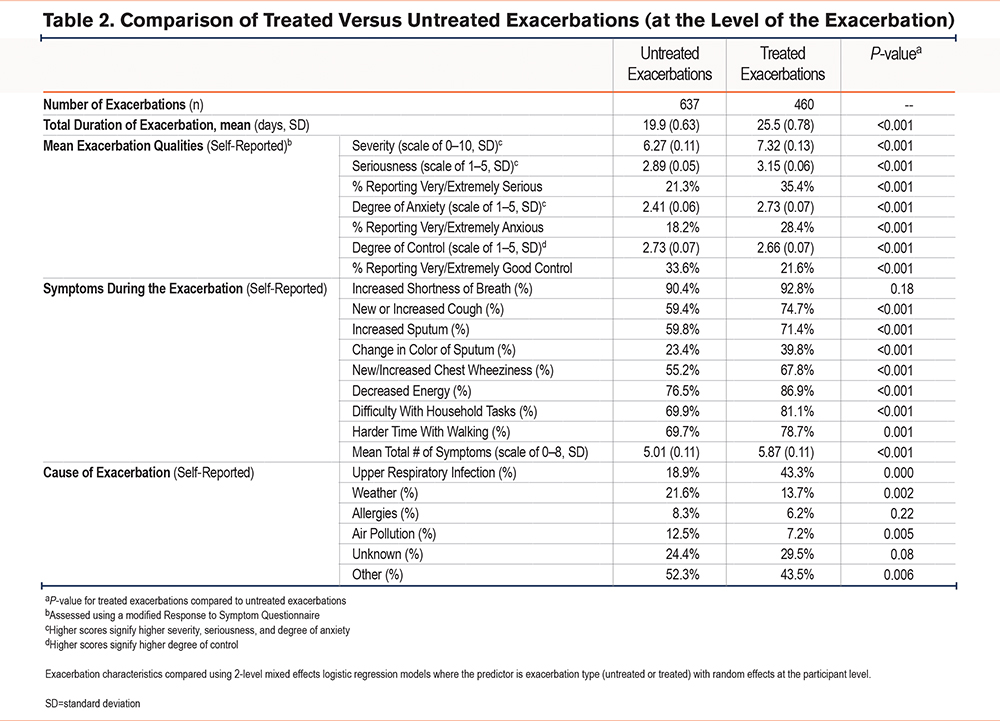

Table 2 compares characteristics of untreated versus treated exacerbations. Treated exacerbations were associated with longer total exacerbation duration as compared with untreated exacerbations (25.5 versus 19.9 days,p-value < 0.001). Treated exacerbations were also associated with increased self-reported severity, seriousness, anxiety, and decreased degree of control (as assessed using the RSQ) compared with untreated exacerbations. Notably, for untreated exacerbations, participants reported that 21.3% of exacerbations were very/extremely serious, and that 18.2% of exacerbations caused them to feel very/extremely anxious. Treated exacerbations had a slightly higher average total number of symptoms compared with untreated exacerbations (5.87 0.11 versus 5.01 0.11 symptoms out of 8 total) (Table 2). Increased shortness of breath was experienced by most participants during both treated and untreated exacerbations (92.8% versus 90.4%,p-value 0.18). All other symptoms including cough (74.7% versus 59.4%,p-value < 0.001) and sputum production (71.4% versus 59.8%,p-value < 0.001) were more common among exacerbations that were treated. Among causes ascribed to the exacerbation by participants, upper respiratory tract infections were more common for those who were treated (43.3% versus 18.9%), whereas weather (13.7% versus 13.7) and air pollution (7.2% versus 12.5%) were less common for treated exacerbations (Table 2).

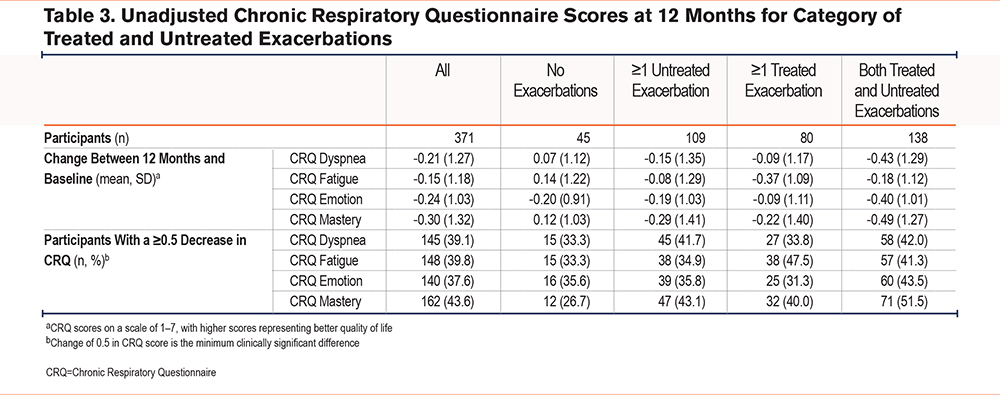

Of the 410 participants who enrolled in the study, 372 (90.7%) completed the follow-up CRQ assessment at 12 months. In unadjusted analyses, all CRQ subscale scores on average decreased at 12 months compared to baseline (dyspnea -0.21; fatigue -0.15; emotion -0.24; mastery -0.30 change), suggesting a decline in average quality of life over one year (Table 3). Furthermore, 39.1% of participants experienced a decrease of 0.5 in their CRQ dyspnea score over 1 year, consistent with a clinically meaningful worsening in long-term HRQoL; similar percentages were seen in the other 3 domains (Table 3).

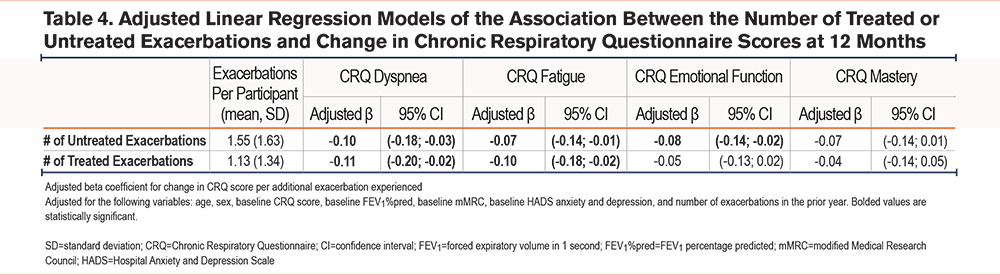

Adjusted linear regression models were performed to evaluate the effect of the total number of either treated or untreated exacerbations on change in CRQ over 12 months (Table 4). Each additional untreated exacerbation was associated with a decline in the CRQ dyspnea score (adjusted β -0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] -0.18 to -0.03), the CRQ fatigue score (adjusted β -0.07; -0.14 to -0.01), and the CRQ emotion score (adjusted β -0.08; -0.14 to -0.02). Each additional treated exacerbation was associated with a decline in the CRQ dyspnea score (adjusted β -0.11; -0.20 to -0.02) and the CRQ fatigue score (adjusted β -0.10; -0.18 to -0.02) (Table 4).

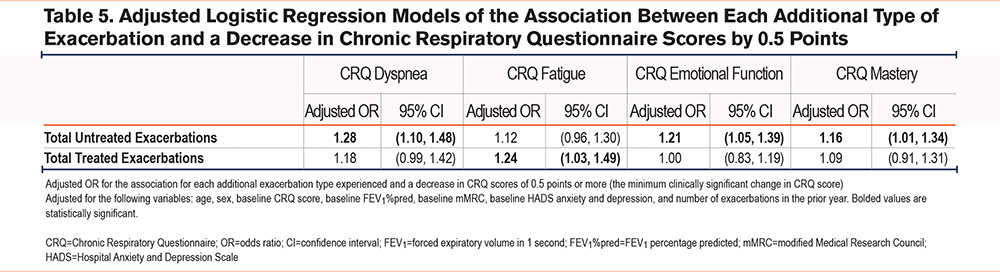

Additionally, adjusted logistic regression models were performed to evaluate the association between each additional exacerbation (treated and untreated) and a decrease in CRQ scores of 0.5 points (the minimally clinically significant change in the CRQ score). Each additional untreated exacerbation was associated with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) for 0.5 decrease in CRQ dyspnea of 1.28 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.48). Similarly, for a decrease in the CRQ emotional function score the adjusted OR was 1.21 (1.05 to 1.39); and for a decrease in the CRQ mastery score the adjusted OR was 1.16 (1.01 to 1.34). For each additional treated exacerbation, only the adjusted OR for a decrease in the CRQ fatigue score 0.5 points at 12 months was statistically significant (1.24; 1.03 to 1.49) (Table 5).

Discussion

Our analyses show both treated and untreated exacerbations are associated with decreased long-term HRQoL. This study builds upon existing literature that shows that untreated exacerbations are a major source of morbidity for COPD patients. We found that for each additional untreated exacerbation, participants reported a statistically significant worsening of CRQ dyspnea, fatigue, and emotional function scores at 12 months. Additionally, each additional untreated exacerbation was associated with an increased likelihood of a clinically significant negative change in CRQ dyspnea, emotional function, and mastery scores at 12 months. This is despite the fact that untreated exacerbations were reported by participants to be somewhat less severe than treated exacerbations, with a lower symptom burden and a shorter duration.

Many studies have demonstrated that patients’ HRQoL decreases shortly after exacerbations occur.12-14 Few studies, however, have assessed the long-term impact of treated and untreated exacerbations on HRQoL. One study that previously assessed the long-term impact of exacerbations on HRQoL was conducted from a cohort of patients in China and found that more than 1 unreported exacerbation was associated with worse HRQoL at 12 months.15 Our findings are consistent with this study, with some important differences. Our study utilizes the CRQ for quality of life, instead of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.15 Our study classified treatments based on participants receiving prednisone or antibiotics, a slightly different approach than the prior study’s delineation of “reported versus unreported” exacerbations. By focusing on those who did not receive treatment, either through their provider or by home treatment, we better identify the impact of untreated exacerbations on HRQoL. Additionally, the prior study found that on average HRQoL improved over 12 months across all participants, whereas our study demonstrated an average decrease in HRQoL, which may be more consistent with the natural course of COPD.14,29

Despite differences in the demographics of the participants, as well as the possibility that treatment and care seeking may differ between health care systems, the results of our study and the prior study both highlight the high proportion of untreated exacerbations in COPD and the adverse impact of untreated exacerbations on HRQoL, assessed with 2 different HRQoL questionnaires. Given that an estimated 50% of COPD exacerbations are untreated,2,10 these findings have tangible clinical implications by reinforcing the importance of preventing exacerbations. There are several important interventions that may reduce the incidence of exacerbations, including medications such as long-acting bronchodilators and ensuring appropriate vaccinations.30 Whether treatment of untreated exacerbations would improve long-term HRQoL is not known; however, earlier use of prednisone and antibiotics is associated with more rapid symptom recovery that could impact COPD-related HRQoL.31

We also examined differences in the characteristics between untreated and treated exacerbations, and found that treated exacerbations were generally more severe, lasted longer, and had more symptoms present compared with untreated exacerbations. Although there is no gold standard for determining or evaluating the relative severity of an exacerbation, we used the number of symptoms present for each exacerbation, which is a commonly used surrogate for severity.12 We also utilized the modified RSQ question on how “bothersome” the exacerbation was as a measure for the severity of the exacerbation.

Untreated exacerbations had an overall high burden of symptoms, with 90% reporting increased dyspnea, 60% increased cough and sputum, 80% decreased energy, and 70% increased difficulty with walking. Nearly a fifth of untreated exacerbations were rated as very or extremely serious, and participants were very or extremely anxious in response to their symptoms. This suggests that for a large proportion of quite serious exacerbations, patients do not seek care in spite of a large symptom burden. A qualitative COPD analysis done in the same cohort found that patients with exacerbations will often initially wait and try different management care strategies at home to see if the exacerbation will resolve, and only seek care if symptoms fail to improve, they develop severe or worrisome symptoms, symptoms last longer than anticipated, or a family member encourages them to seek care.32 Other studies have found that reasons for not seeking care include lack of recognition that an exacerbation is occurring, wanting to avoid hospitalizations, not wanting to bother the health care team, lack of continuity of care, or difficulty traveling to the health care facility.5,33-36 Self-management programs that include an emphasis on early detection, acceptance of symptoms, and an action plan for exacerbations are an approach to encourage treatment of exacerbations, which may help to reduce their impact on HRQoL.37

This study has several limitations. CRQ scores were only obtained twice during the study period, at the beginning and at the end of the 12-month follow-up. This study was conducted within the VA patient population, which is mostly male and generally older, and therefore, may not necessarily be widely applicable across all demographics. Similarly, the inclusion criteria for this study resulted in a study population with more severe COPD, and all participants had at least 1 exacerbation in the year prior. These study results may not necessarily be applicable for patients with milder COPD. Finally, we did not define untreated exacerbations based on daily diaries, which would not have been possible for a large sample of participants followed for 12 months, but instead called participants every 2 weeks to identify exacerbations to minimize recall bias.

Conclusion

We found that untreated COPD exacerbations occurred frequently and were associated with worse long-term HRQoL, measured with the CRQ, compared to those without exacerbations. This is despite the fact that untreated exacerbations were associated with lower symptom burden and shorter duration as compared to treated exacerbations. Therefore, all exacerbations, even those that go untreated, may contribute to long-term symptom burden and morbidity for patients. Preventing COPD exacerbations, as well as prompt treatment of exacerbations when they occur, may help mitigate decreases in long-term HRQoL.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: NW contributed to the conception and design of this original analysis from an existing data set, assisted with data analysis and interpretation, and was the primary writer of the manuscript. EL contributed to the design of this original analysis, assisted with acquiring the original data, and was the primary data analyst and assisted with data interpretation. TS, ES, JE, and RT contributed to the initial conception and design of the original data set and assisted with the conception and design of this original analysis. VF contributed as the primary investigator behind the original data set (conception, design, implementation, and data acquisition), directly contributed to the conception and design of this original analysis, assisted with data analysis and interpretation, and assisted with writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript submitted for publication.

Other acknowledgements: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Declaration of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, and have no financial disclosures, with regards to the findings described in this manuscript.