Running Head: USMI and LSMI as Skeletal Muscle Indices in COPD

Funding Support: None

Date of Acceptance: November 12, 2025 | Published Online Date: December 3, 2025

Abbreviations: ADL=activities of daily living; BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1%pred=FEV1 percentage predicted; FVC=forced vital capacity; GOLD=Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HOT=home oxygen therapy; ISWD=incremental shuttle walking distance; LL=lower limb, LSMI=lower limb skeletal muscle mass index; METs=metabolic equivalents of tasks; mMRC scale=modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale; MMSE=Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA-SF=Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form; MOCA-J=Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Japanese version; NRADL=Nagasaki University Respiratory ADL questionnaire; SMI=skeletal muscle mass index; SMM=skeletal muscle mass; UL=upper limb; USMI=upper limb skeletal muscle mass index; VIF=variance inflation factor

Citation: Oba J, Kotani S, Kubo S, Horie J. Upper and lower limb skeletal muscle mass index as a novel evaluation index in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2026; 13(1): 8-16. doi: http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2025.0698

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is known to cause systemic impairments that extend beyond the lungs. Therefore, COPD is recognized as a respiratory disease and a systemic inflammatory disorder. This systemic involvement is mediated by inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which contribute to skeletal muscle dysfunction.1 Among these systemic changes, patients with COPD have been reported to have significantly lower fat-free mass and fat-free mass index compared to individuals without COPD.2 Furthermore, regardless of the severity of dyspnea or degree of airflow limitation, decreased quadriceps strength3 and reduced quadriceps cross-sectional area4 have been reported. Regarding upper limb function, handgrip strength—a representative indicator of upper limb muscle strength—has not always been found to differ significantly between patients with COPD and those without COPD after adjusting for age, sex, and height.5 However, during acute exacerbations, patients with COPD demonstrate lower grip strength compared with individuals without or with stable COPD.6 Muscle fiber alterations, such as a reduction in type 1 fibers and an increase in type 2 fibers, have also been reported.7 Moreover, depletion of skeletal muscle mass (SMM) has been associated with prognosis, as reductions in SMM are linked to higher in-hospital mortality during exacerbations.8,9 SMM is an important parameter in evaluating muscle loss associated with aging and disease. In fact, the assessment of appendicular skeletal muscle mass index (SMI) is a mandatory criterion for the diagnosis of sarcopenia.10 Previous studies11 have reported that the prevalence of sarcopenia among patients with COPD is 21.6%, emphasizing the clinical importance of SMM assessment. Given this background, the evaluation of appendicular SMM is considered crucial in pulmonary rehabilitation. Handgrip strength, as an indicator of upper limb muscle strength, has been shown to be associated with physical activity and exercise capacity.12-14 Furthermore, decreased handgrip strength has been linked to an increased risk of acute exacerbations15 and poorer prognosis.16 Similarly, lower limb muscle strength has also been reported to be associated with physical activity and exercise capacity.17,18 In clinical practice, pulmonary rehabilitation often emphasizes interventions targeting the lower limbs, including strength training and aerobic exercise. Aerobic training, typically consisting of walking and cycle ergometer exercise, primarily engages the lower limbs. Because daily activities are largely based on ambulation, lower limb training is prioritized in pulmonary rehabilitation programs. Although reports have linked upper and lower limb muscle strength with physical activity and exercise capacity, no studies to date have specifically examined the relationships between upper and lower limb SMM and these outcomes in patients with COPD. Clarifying these relationships may provide new perspectives in pulmonary rehabilitation and highlight the importance of evaluating SMM. Bioelectrical impedance analysis, a method used to measure SMM, offers a simple and feasible screening tool in clinical practice. In addition, assessing physical activity not only by step count but also by including exercise volume and intensity may enhance patient education strategies aimed at improving physical activity levels. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the relationships and usefulness of physical activity, physical performance, and physical function in patients with COPD, focusing on 2 newly proposed skeletal muscle indices: the upper limb skeletal muscle mass index (USMI) and the lower limb skeletal muscle mass index (LSMI).

Participants and Methods

Participants

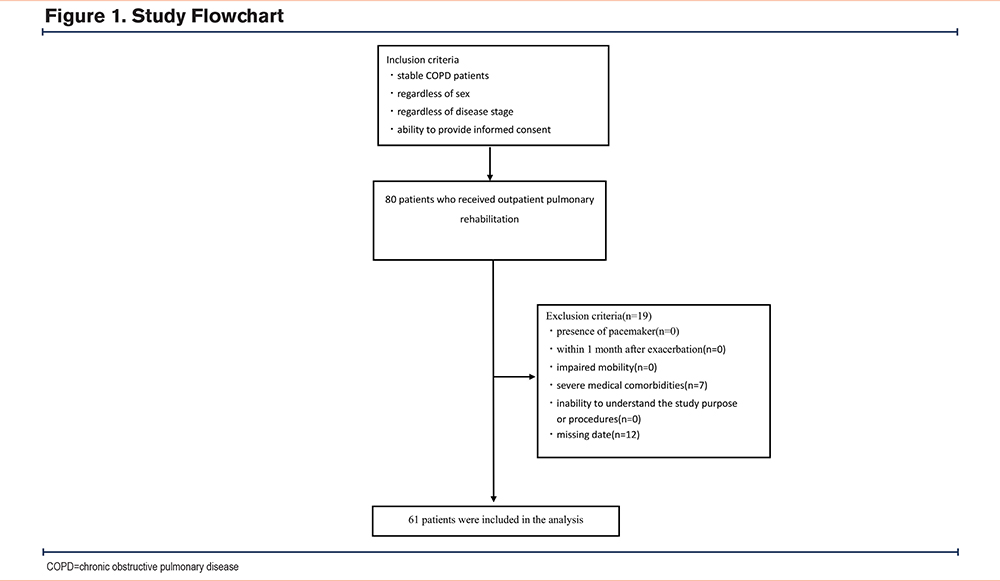

The participants were 80 stable outpatients with COPD who were enrolled in a pulmonary rehabilitation program at Osaka Fukujuji Hospital (mean age, 75.4±7.9 years; 71 men and 9 women). Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of stable COPD, regardless of disease stage or sex, and the ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: (1) presence of a pacemaker, (2) less than 1 month since last exacerbation, (3) impaired mobility, (4) severe medical comorbidities, (5) inability to understand the study purpose or procedures, and (6) incomplete data.

Methods

Measurement Indices

The primary measurements included the USMI, LSMI, and the overall SMI. These parameters were measured using a bioelectrical impedance analyzer (InBody270Ⓡ, InBody Japan; Tokyo, Japan). Explanatory measurements included physical activity, which was assessed using a triaxial accelerometer (Active style ProⓇ, Omron Corporation; Kyoto, Japan). The device recorded step counts, walking time, weekly exercise volume, daily exercise volume, walking exercise volume, lifestyle exercise volume, time spent in activities <3 metabolic equivalents of task (METs), and time spent in activities ≥3 METs. Physical performance and function were assessed using upper limb SMM, lower limb SMM, and the incremental shuttle walking distance (ISWD) test. Lower limb muscle strength was measured as maximal isometric knee extension force (μTas F-1Ⓡ, ANIMA; Tokyo, Japan). Upper limb muscle strength was measured using maximal handgrip strength with a digital handgrip meter (Digital Hand Grip MeterⓇ, Takei Scientific Instruments; Niigata, Japan). Activities of daily living (ADL) were evaluated using the Nagasaki University Respiratory ADL questionnaire (NRADL). Pulmonary function was assessed by forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1 percentage predicted (FEV1%pred), and the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC).

Calculation of Upper Limb Skeletal Muscle Mass Index and Lower Limb Skeletal Muscle Mass Index

The USMI was calculated as the sum of the SMM of the left and right upper limbs (kg), measured using a body composition analyzer, divided by height squared (m²). Similarly, the LSMI was calculated as the sum of the SMM of the left and right lower limbs divided by height squared (m2). These indices adjusted for body size and were used to evaluate region-specific SMM.

Measurement of Physical Activity

Each participant was instructed to wear a triaxial accelerometer continuously for one month, after which the device was collected. To avoid intentional increases in physical activity, the device display was configured so that step counts and other metrics were not visible to participants. The accelerometer was attached to the waistband of the trousers and worn throughout the day, except during bathing and sleeping. Data were analyzed using dedicated software, and days with less than 360 minutes of wear time were excluded from the analysis.

Nagasaki University Respiratory Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire

The NRADL is a respiratory disease-specific ADL questionnaire developed in Japan. It evaluates activities of daily living in 4 categories: movement speed, dyspnea, oxygen flow rate, and continuous walking distance. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 3 (except for continuous walking distance, which is scored from 0 to 10). The total score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater independence in ADL.

Statistical Analysis

Associations between USMI, LSMI, SMM variables, and explanatory measures were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. A correlation coefficient ≥0.40 was considered clinically relevant.19 To identify independent determinants of USMI, LSMI, and SMI, multiple regression analyses with stepwise selection were performed. Independent variables included step counts, weekly exercise volume, time spent in activities ≥3 METs, ISWD, FEV1%pred, and age.11,20,21 Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 30 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, New York).

Ethical Considerations

This study was a retrospective study using data obtained from routine clinical practice and was conducted in an opt-out manner. In addition, this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kyoto Tachibana University (approval number: 25-4).

Results

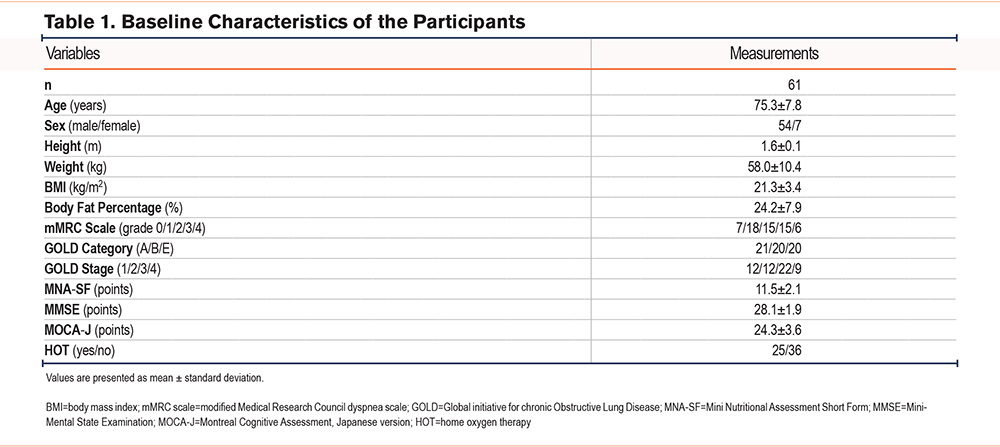

The participant flow is shown in Figure 1. A total of 61 participants were included in the final analysis. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 75.3±7.8 years, and 54 participants (88.5%) were male. The mean body mass index was 21.3±3.4 kg/m2. Distribution across the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)22 categories was balanced, with 21 participants in group A, 20 in group B, and 20 in group C.

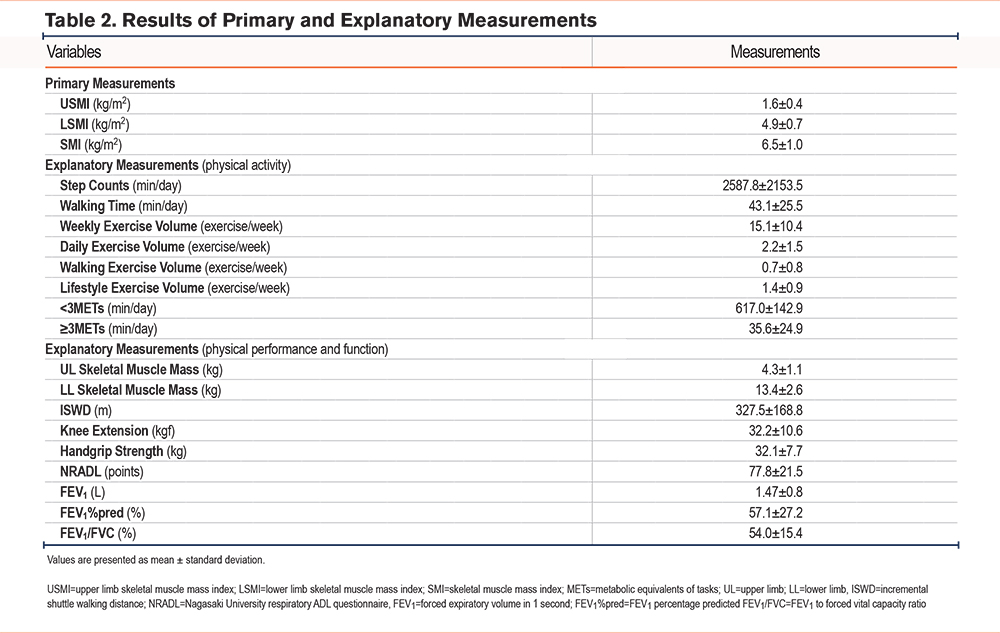

Table 2 shows the results of primary and explanatory measurements. The mean values were as follows: USMI, 1.6±0.4; LSMI, 4.9±0.7 kg/m²; upper limb SMM, 4.3±1.1 kg; lower limb SMM, 13.4±2.6 kg; and SMI, 6.5±1.0. Regarding physical activity, the mean step count was 2587.8±2153.5 steps/day, weekly exercise volume was 15.1±10.4 exercise/week, time spent in activities <3 METs was 617.0±142.9 min/day, and time spent in activities ≥3 METs was 35.6±24.9 min/day. The mean ISWD was 327.5±168.8 m, and the FEV1%pred was 57.1±27.2%.

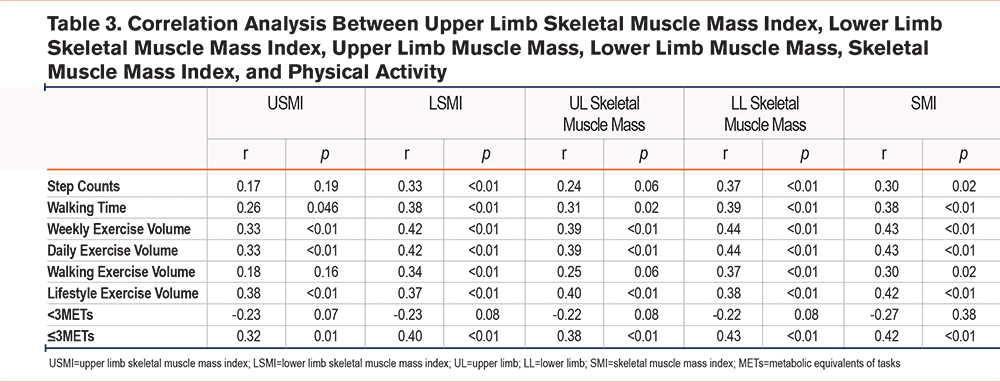

Table 3 presents correlations between skeletal muscle indices and physical activity. USMI was not significantly correlated with any physical activity variables. LSMI was significantly correlated with weekly exercise volume (r=0.42, p<0.01), daily exercise volume (r=0.42, p<0.01), and time spent in activities ≥3 METs (r=0.40, p<0.01). Upper limb SMM was correlated only with lifestyle exercise volume (r=0.40, p<0.01). Lower limb SMM was significantly correlated with weekly exercise volume (r=0.44, p<0.01), daily exercise volume (r=0.44, p<0.01), and time spent in activities ≥3 METs (r=0.43, p<0.01). SMI was significantly correlated with weekly exercise volume (r=0.43, p<0.01), daily exercise volume (r=0.43, p<0.01), lifestyle exercise volume (r=0.42, p<0.01), and time spent in activities ≥3 METs (r=0.42, p<0.01).

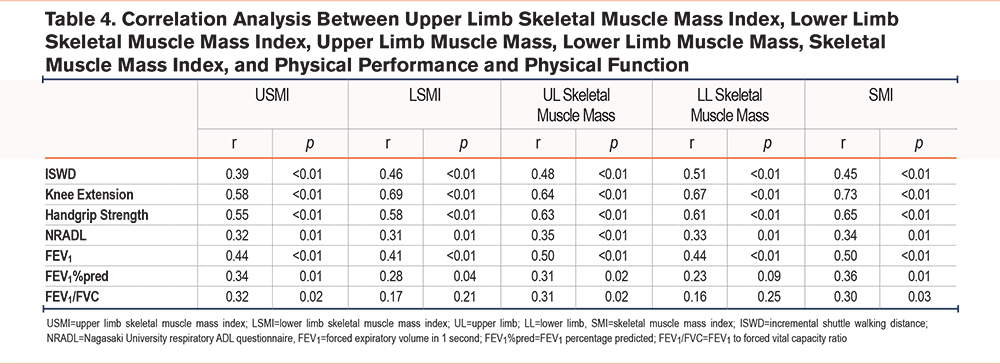

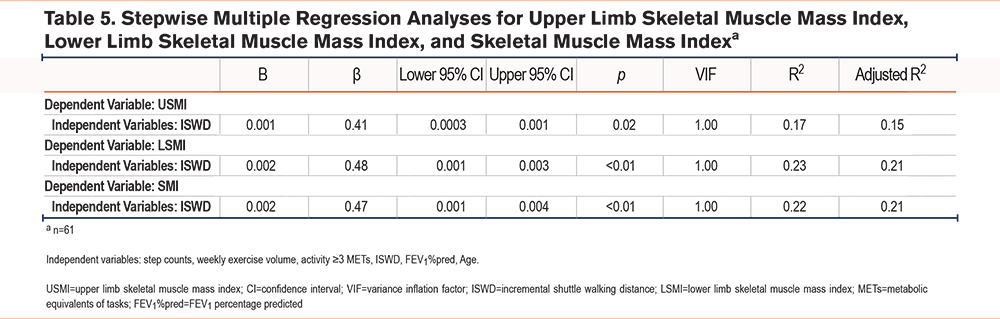

Table 4 shows correlations between skeletal muscle indices and functional outcomes. USMI was significantly correlated with knee extension strength (r=0.58, p<0.01), grip strength (r=0.55, p<0.01), and FEV1 (r=0.44, p<0.01). LSMI was correlated with ISWD (r=0.46, p<0.01), knee extension strength (r=0.69, p<0.01), grip strength (r=0.58, p<0.01), and FEV1 (r=0.41, p<0.01). Upper limb SMM was correlated with ISWD (r=0.48, p<0.01), knee extension strength (r=0.64, p<0.01), grip strength (r=0.63, p<0.01), and FEV1 (r=0.50, p<0.01). Lower limb SMM was correlated with ISWD (r=0.51, p<0.01), knee extension strength (r=0.67, p<0.01), grip strength (r=0.61, p<0.01), and FEV1 (r=0.44, p<0.01). SMI was correlated with ISWD (r=0.45, p<0.01), knee extension strength (r=0.73, p<0.01), grip strength (r=0.65, p<0.01), and FEV1 (r=0.50, p<0.01). Table 5 presents the results of stepwise multiple regression analyses for USMI, LSMI, and SMI. ISWD was identified as an independent determinant for all 3 indices. For USMI, ISWD was a significant predictor (B=0.001, β=0.41, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.000–0.001, p=0.02), with an adjusted R² of 0.15. For LSMI, ISWD was also a significant predictor (B=0.002, β=0.48, 95% CI: 0.001–0.003, p<0.01), with an adjusted R² of 0.21. In addition, for SMI, ISWD was identified as a significant predictor (B=0.002, β=0.47, 95% CI: 0.001–0.004, p<0.01), with an adjusted R2 of 0.21. Across all analyses using USMI, LSMI, and SMI, independent variables such as step counts and weekly exercise volume were expected to be correlated. However, in the final models, only ISWD was retained, and the variance inflation factor was 1.00, indicating that multicollinearity was not an issue.

Discussion

This study examined the associations and usefulness of the USMI and LSMI with physical activity, physical performance, and physical function in patients with COPD. While previous studies have commonly used SMM or the SMI,23 our study newly introduced USMI and LSMI as region-specific indices. The findings demonstrated that USMI was not significantly correlated with physical activity or exercise tolerance. Upper limb SMM was correlated only with lifestyle exercise volume. In contrast, LSMI and SMI showed significant correlations with weekly exercise volume, daily exercise volume, and time spent in activities ≥3 METs. Similarly, unadjusted lower limb SMM also demonstrated significant associations. LSMI demonstrated correlations comparable to those of SMI, suggesting that LSMI may possess validity equivalent to the established SMI while more accurately reflecting its associations with physical activity. This suggests that LSMI may serve as a more reliable indicator than absolute muscle mass when assessing patients with different body constitutions. These results reflect the fact that daily activities in COPD predominantly involve lower limb–driven movements such as walking, while upper limb muscle mass contributes less to overall activity. Therefore, interventions aimed at improving physical activity should prioritize the preservation and enhancement of lower limb muscle mass. LSMI, a novel index developed to reflect lower limb SMM, has not yet been investigated for its clinical utility in patients with COPD. However, the present findings suggest that it may represent a clinically meaningful indicator in the assessment of physical activity in this population. Step count, a conventional measure of physical activity, was not significantly correlated with USMI, LSMI, or SMI. However, significant associations were observed with exercise volume and time spent in activities ≥3 METs. This finding indicates that quantitative walking measures alone are insufficient, and activity intensity and overall daily activity must also be considered. Previous studies have shown that patients with COPD exhibit reduced activity intensity compared with healthy individuals,24 and the present results further emphasize the importance of promoting intensity-based activities. Thus, pulmonary rehabilitation and patient education should address not only increasing step count but also exercise volume and activity intensity. Regarding exercise tolerance, USMI was not correlated with ISWD, whereas LSMI and SMI demonstrated significant correlations and were independently associated with ISWD in multiple regression analysis. The magnitude of this association was greater for LSMI and SMI than for USMI, suggesting a closer relationship between LSMI and SMI and exercise tolerance. Prior studies have reported associations between fat-free mass and exercise capacity,25,26 and our findings support this by showing a correlation between SMI and ISWD. However, the absence of an association with USMI and the presence of a strong association with LSMI and SMI indicate that lower limb muscle mass, rather than upper limb muscle mass, plays a central role in exercise tolerance in COPD. This is consistent with the fact that aerobic training in pulmonary rehabilitation primarily involves lower limb activities such as walking and cycling, and that a decline in LSMI may directly contribute to reduced exercise tolerance. While upper limb muscles are important for activities of daily living such as grooming, eating, and household tasks, they have limited influence on endurance and walking ability. The independent association between LSMI and SMI with ISWD observed in this study underscores the critical importance of lower limb muscle mass in maintaining and improving exercise tolerance in COPD. This study has some limitations. First, most participants were men, which prevented an adequate evaluation of sex-specific effects. As men generally have greater muscle mass than women, this imbalance may have influenced the results. Second, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Longitudinal studies are warranted to confirm these findings. In addition, it will be important to further examine these relationships in patients with severe COPD, who are known to have reduced SMM. Furthermore, to facilitate clinical application, interventional studies incorporating pulmonary rehabilitation should be conducted to determine how changes in LSMI contribute to improvements in physical activity and exercise tolerance. This study demonstrated that LSMI, similar to SMI, is associated with physical activity and exercise tolerance in patients with COPD. Incorporating simple assessments of LSMI into pulmonary rehabilitation programs may facilitate individualized exercise prescription and strengthen patient education.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the LSMI is associated with both physical activity and exercise tolerance in patients with COPD, similar to the SMI. In particular, LSMI was significantly related to activity measures that accounted for intensity as well as to exercise tolerance, whereas the USMI showed no such associations. These findings highlight the importance of evaluating lower limb muscle mass in pulmonary rehabilitation and suggest that LSMI, similar to SMI, may serve as a valuable clinical index for individualized patient assessment.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: JO conceived and designed the study, collected the data, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. SKotani contributed to data collection and assisted with data analysis. SKubo contributed to data collection. JH contributed to data collection, provided supervision of the study, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Other acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge Editage for English language editing.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.